The last words Anthony Mitchell Sr. said to his oldest son were that he was still waiting for an ambulance as the Eaton fire raged through his Altadena home.

“He called everyone and said, ‘It’s okay, we’re just waiting for you to evacuate,'” Mitchell, a junior, said of the 5 a.m. call. “He probably knew no one was coming, but he wanted to reassure everyone.”

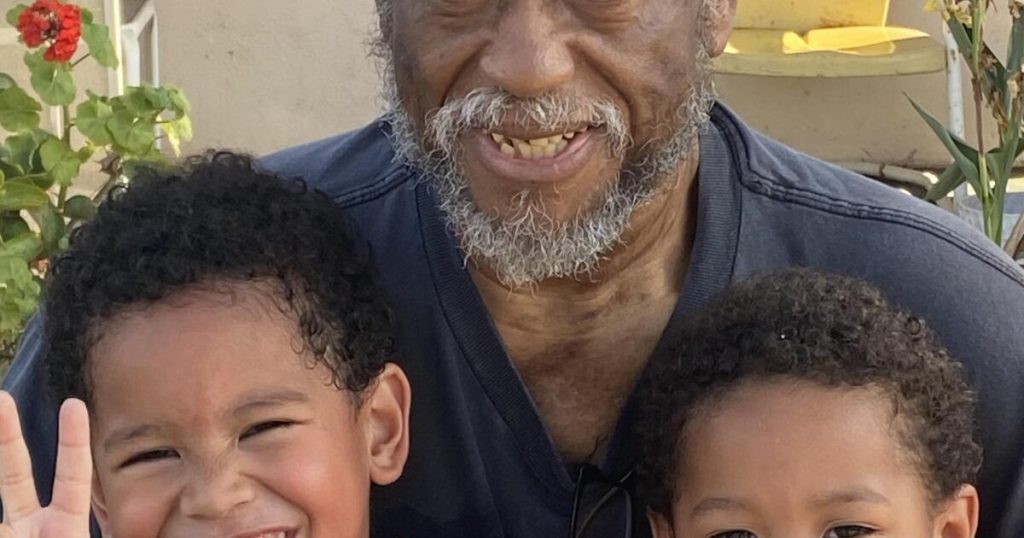

The great-grandfather and patriarch of the Mitchell family had an amputee and used a wheelchair. His son Justin Mitchell has cerebral palsy and needed help getting out of bed. They were unable to escape on their own and relatives said firefighters stopped them from entering the evacuation zone.

“He could have gotten up and left, but he’s not going to leave his brother,” Mitchell said. “My father was never going to leave his children. His children were his legacy.”

There, they huddled together and waited for help to arrive, becoming two of the first victims of an unprecedented firestorm still raging across Los Angeles County. Authorities announced Friday that at least 11 people were killed in the disaster.

“The most painful thing is that the state was completely unprepared for this,” Mitchell said.

Officials have known for years that people with disabilities in California are disproportionately likely to die in wildfires. In 2019, the state released a scathing audit detailing how emergency management agencies and other first responders were unprepared for the threat.

At the time, it was estimated that approximately 4 million Californians had disabilities, including nearly 250,000 Angelenos under the age of 65.

Many say they feel even more vulnerable now.

“I feel helpless,” said actress and singer Josi Scott, 26, a wheelchair user who lives in North Hollywood. “People with disabilities are usually forgotten in the evacuation process. It’s much more difficult for us.”

Data shows that Black residents like the Mitchells are far more likely to be disabled than white, Latino, or Asian residents. They were among those who could not evacuate without help. Some, like Scott, are reluctant to flee because they know they can’t carry the tools they rely on to breathe, move, eat, bathe and use the toilet, and most shelters won’t have access to them.

“I have important medications that I cannot live without and mobility equipment that is very expensive and difficult to replace,” Scott said. “It’s really overwhelming.”

Even small, relatively inexpensive prescription medications like urinary catheters can be difficult to find, especially in an emergency, the actress said. But without them, “I’m immediately at risk for kidney infection and sepsis.”

Her fears are familiar, said German, co-executive director of the Comprehensive Disaster Strategy Partnership and a central figure in the disability and disaster hotline that has been fielding calls from people evacuated from the Los Angeles fires. Parodi said.

“There’s a fear of not knowing where to go or what to bring,” he says. “The sooner organizations like mine can identify needs, the sooner we can ensure that products are locally sourced.”

Parodi said state and federal disaster officials can be contacted directly. He and others also work closely with the Center for Independent Living in Los Angeles, which can quickly get oxygen tanks and wheelchairs to Angelenos in need.

“Our center provides disaster planning and resources,” says Renee Nash, an outreach worker who lives independently, freely and actively in a downtown Los Angeles community. “If you need motel coupons, if you need access to Uber or Lyft, we’ll do it for free.”

It will also provide battery banks to people who need to keep medical equipment running when thousands of people in LA lost power this week.

“If you’re on an oxygen concentrator or Hoyer lift, Edison will deliver battery backup for the Goal Zero Yeti so you can connect your medical equipment,” Nash explained. “People say they’re doing a great job.”

However, major obstacles remain, especially when it comes to evacuation.

“Roads are blocked and no one can come to help,” said Sera Rea, Disability Access and Resources Program Manager for the California Independent Living Foundation.

Many people with disabilities cannot drive or have access to a car. Some people worry that they will be stuck in traffic and burned alive in their cars.

“A few days ago, I saw many people having to get out of their cars and run for their lives,” Rea said. For some people with disabilities, that is not an option.

Recent glitches in emergency alert systems only add to the fear.

“I can’t just jump out of bed and run. I have to find someone to carry me down the stairs,” said Tamara Mena, a wheelchair user who lives in Northridge. The elevator in her apartment stopped working due to a power outage. “Every minute counts.”

Some complained of a lack of communication from officials.

“If people weren’t sharing these resources, I wouldn’t have known about them. I think this is messed up in a way,” Scott said. “This information should already be widely known.”

City, state, and federal governments have offices responsible for ensuring that people with disabilities are not left behind during disasters. Officials in each declined to request comment.

For Mitchell, the pain of losing his father and brother is tinged with anger at the way they died.

“I’m angry about what happened to my dad, because it shouldn’t have happened,” he said. “The institution has failed him.”

Source link