[ad_1]

Before Joseph Wanbaugh arrived, the unofficial bard at the Los Angeles Police Department was Jack Webb, the tiny sergeant. Joe Friday haunted every episode of “Dragnet” with symbols of moral weakness and crime.

“Marijuana is a fire, heroin is a fuse, and LSD is a bomb,” was seen by the suspect on a 1967 episode on Friday. “So don’t try to identify liquor with marijuana, Mr., not me. …Would you condol me with your heart and slop of expansion!”

Then came Wambaugh, a veteran of LAPD. The fictional officer would have been screaming out California criminal law and bottles of sanitizer on Friday. Wanbo’s character was morally flexible, heroic, abominable, caring, cold, deeply flawed, dark and comical.

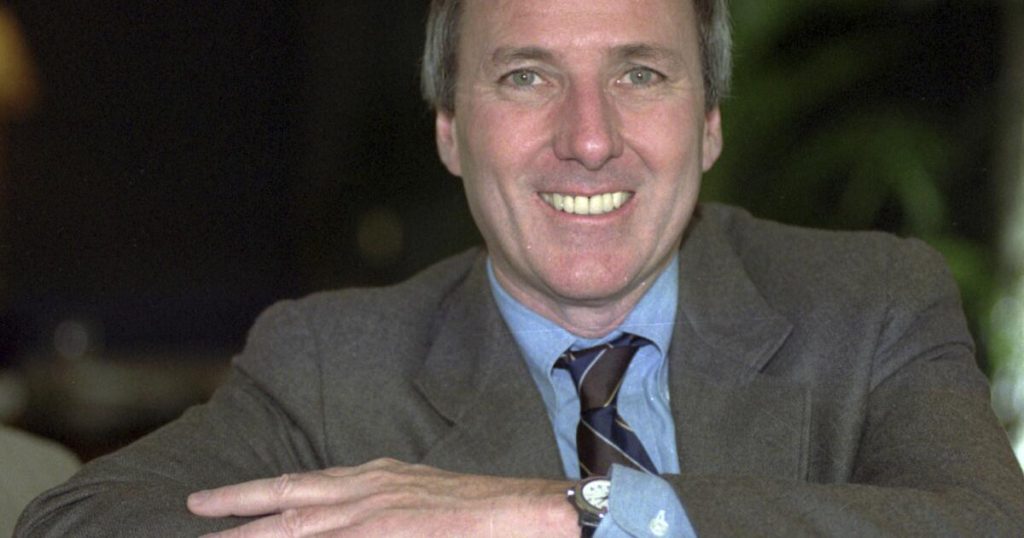

With 16 novels and five non-fiction crime stories changing the portrayal of American policemen, Wanbaugh paved the way for gritty television shows such as “Hill Street Blues” and “NYPD Blue,” and passed away Friday at his home in Rancho Mirage, California. He was 88 years old.

His death was caused by esophageal cancer, Gantt said. He had been learning about his illness about 10 months ago. Dee, his 69-year-old wife, was by his side, Gantt said.

His bestselling novels included “The New Centurions,” “The Glitter Dome,” “The Choirboys,” and “Black Marble.” The best known of his non-fiction works was “Onion Field.” This was a horrifying story that began with the routine halt of illegal U-turns and quickly led to the execution of Los Angeles police officers on the field in Kern County.

Michael Connelly, a former Los Angeles Times police reporter who became the author of acclaimed crime novel, said he came to consider Wanbaugh as a mentor 25 years before he actually met him and became friends.

Before Wanbou, crime novelists often focused on “a lonely detective whom he has distrust and even spews.”

“To Wanbaugh, he shot the story inside the police station and inside the police car it really belonged to, to tell the story of a man who put their lives and sanity at risk to do it. And to explore different kinds of corruption – the premature irony of a police officer who appears too often in the dark bys of mankind, too long and too long.”

Wanbo said that in a simple way.

“What I did was to turn things around,” he told the San Diego Union Tribune in 2019.

Every turn, Wanbaugh defeated the convention. The crime may or may not be resolved. The bad guys may or may not meet justice. And the police themselves may be a tough, square expert with straight arrows.

After leaving LAPD 14 years later, Wambaugh left as a detective sergeant to pursue his writing career, he was particularly tough on departmental bureaucrats and top brass.

In “Choir”, he fails his assigned secret mission: sneaks into the department’s personnel file and changes the ambitious boss’ IQ score from 107 to 141. However, he exchanges himself as an administrator by writing an unforgettable new rules about executive sideburns and fatal scale.

“It took EUs 13 weeks to create regulations during the treadwell,” Wanbo wrote. “He was toasted and congratulated at the staff meeting. He was proud. The regulations were perfect. No one could understand them.”

The bay between Wanbou’s labor officers and their best leader was enormous. IQ-absent commander Moss said, “If anyone has organized ignorant bastards, I’ll look at them. Commander Moss was like a slave who lived in fear of the native footsteps of the deck at night.”

Of course, some of Wanbaugh’s street policemen had dementia.

In “The Delta Star,” a giant, permanently angry officer known as Bad Czech follows a small thief in downtown LA, trying to squeeze him out of the fire escape.

Later in the story, he catches up to a violent serial robber who is stabbed and brought to life. The officer bends beside him, “runs CPR” violently, pumping almost every time he squeezes blood from the dying villain’s body.

He is appropriately humble when an elderly witness thanked him for bravely trying to save the lives of criminals.

“Thank you, ma’am,” the bad Czech said embarrassedly. “It’s not painful to remember that we all remember God’s children.”

Even the delusions and deserts depicted very vividly by Wanbaud, an unknown act of goodwill and kindness emerges through the blue mist. The city of Los Angeles, especially Hollywood, is a background for not only cults that fetish addicts, con artists, traffickers and amputees, but also for those suffering and police officers who help them.

In “Harbor Nocturne,” a perky 91-year-old woman seeks help in waking up her husband, Howard.

“He always takes an afternoon nap,” she says, Nate Weiss of Hollywood, an executive with a SAG card and always looking for a big break in the movie. “This time it’s a long nap.”

Hollywood Nate and his shy young partner Britney Small were patrolling on their cruiser, discussing their horrifying dreams. Nate has a recurring vision of a murdered partner, a woman with a “laughter that sounds like a wind chime.” Britney is pissed off by the admiration she brought her from more seasoned cops, plagued by the attacker she was shot.

A few minutes later, they comforted the attacked widow, holding her hand, showing old photos of their family trip to the Grand Canyon. Britney then cried, soft, hard-boiled Hollywood Nate softened her.

The two are one of a handful of characters, like Flossom and Jessam, surfer detectives who reappear in Wambaugh’s work. In “Hollywood Hills,” the small officer confronts a man who talks to himself and pours drinks into ur at a former elegance bar.

The man was taking his father’s ashes to drink. Britney told him to put his father on a dark corner table where he wouldn’t confuse other customers.

“Dad loved standing at the bar with his feet on the rails,” explained the sad son.

“I understand that, sensei,” the officer said. “But he had his leg at the time.”

Born on January 22, 1937, Joseph Aloysius Wanbo Jr. grew up in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where his father worked in a steel factory and for some time was the city’s police chief. When Joseph was 14, his family decided to come to California to stay for a funeral.

After graduating from high school in Ontario, Wanbaugh served in the Marines from 1954 to 1957 before completing his Bachelor of Arts in English from Los Angeles, California. He wanted to teach, but there was more LAPD than in school.

When he rose to rank, he received his master’s degree from Cal State. He also hid notes about his experiences on the streets and defied departmental rules, turning them into his first novel, The New Centurions.

When Chief Ed Davis heard about the pending publication, he threatened to fire Wanbaugh. The ACLU takes up his cause and Jack Webb says that if Wanbaugh’s work is worth it, he will intervene with the Chief.

“My murder partner and I drove to Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills and dropped the manuscript,” recalls Wanbaugh to the royal Canadian Mount Police Quarter. A few weeks later, Webb read it and pasted a paper clip with any passages that might piss off the higher ones. “I held the paper clip,” Wanbo said, “and I’ve never met Webb.”

The 1971 novel was the book of this month’s Club Selection and remained on the New York Times bestseller list for 32 weeks. George C. Scott became a film as the benevolent elderly cop Andy Kilbinski. During his retirement, Kilbinsky commits suicide.

Still working officers – “condemned” in place of fire, but Wanbaugh appeared alongside “Blue Knight” in 1972 and “Onion Field” in 1973. For the latter, 63 people interviewed and cultivated more than 40,000 pages of transcripts from one of the long-standing murder trials in California.

The 1963 adduction of LAPD officers Ian Campbell and Karl Hettinger became Wanbaugh’s obsession. His fascinating account of Campbell’s death and Hettinger’s crushing depression is likened to Truman Capote’s “cold blood,” with both authors applying the novelist’s storytelling techniques to cold facts.

“I was placed on Earth to write ‘Onion Fields’,” Wang Beau told NPR. “That’s how I felt about it.”

However, living in LAPD is becoming more and more difficult. Those arrested by Wanbaugh had asked him for the role of the popular television series “Police Story,” which he created for NBC. The suspected man he was handcuffing turned to him and asked, “Do you really like George C. Scott?”

“Man, I have to go outside,” Wang Bo said.

Wanbo left LAPD in 1974. He has abandoned his pension hopes, but has become one of America’s most popular authors, earning an early estimate of at least $1 million per book.

Wambaugh and his family moved from San Marino to Newport Beach, Rancho Mirage, and up to Point Loma near San Diego. Along the way, he wrote crime novels focused on Orange County Yacht Sets, Upper Crust Dog Show Fans, Palm Springs Country Club, America’s Cup and the Nobel Prize.

Instead of exclusively portraying his own LAPD experience, he bought drinks for half a dozen police officers at once, taking abundant notes as they told their stories. With the acknowledgements of “Hollywood Hills,” he thanked 51 officers in four divisions.

In addition to “Onion Field,” Wambau’s non-fiction includes “Line and Shadow” about the San Diego Police Department’s undercover investigation to protect immigrants from human predators. “Echoing in the Dark” about the murder of a Pennsylvania teacher and her two children. “The Blowsing,” on the use of genetic fingerprints to catch British murderers. “Fire Trucks” about firefighters and gardeners in Glendale.

“If it’s non-fiction, I’ll talk to people who lived it,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I’m out there. I haven’t done these interior monologues on 330 pages.

Four of Wambaugh’s works have been transformed into feature films. This was a very infuriating process for the author, and helped two of them to have more control over the outcome. He was so infuriated by the film version of “The Choir” that he bought a daily variety of full-page ads for Lambaste Lorimar Productions and director Robert Aldrich.

During the UCLA panel discussion on the nature of evil in writing crime, Wanbo recalled the day he met it. His first encounter with evil was when I sold my first book to a Columbia photograph,” he said.

Wanbo’s survivors include his wife Dee, a high school lover who married in 1955. daughter Janet; and son David; Another son, Mark, died in a 1984 car accident in Mexico.

He was asked how he wanted to remember, and Wanbaugh summed it up with the nonsense crunch of a patrolman handing out tickets for speeding.

“A police writer,” he said. “That should work.”

Chawkins is a former Times staff writer.

[ad_2]Source link