[ad_1]

We humans, if we lead a life of intentional and thoughtfulness, we almost always go back to a series of timeless questions. Who are we? Where did you come from? where are you going? Some people rely on religion to answer these questions. Some of the psychology. Some of the literature. Others in history, philosophy, and art.

I spent 30 years as a history professor trying to answer basic questions about California and its people’s history. That work was largely possible by the National Fund for the Humanities, a small, underfunded government agency that was hampered by President Trump and his Department of Government Efficiency.

While it is impossible to quantify the important role NEH played in a national search for meaning and self-awareness, Endowment’s website begins to tell stories. Since its establishment by Congress in 1965, NEH has funded more than 70,000 projects in all 50 states. It allowed for the research and publication of 9,000 books, including 20 Pulitzer Prize winners, the creation of 500 films and media programs, the editing and publication of 12 US presidents’ papers, and the editing and publication of towering figures such as Mark Twain, Thomas Edison, Willa Casser, Martin Luther King Jr. and Ernestway.

In creating an organization, Congress sought to affirm and acknowledge that healthy democracy “requires citizen wisdom and vision” and that the federal government must provide “full value and support” to the humanities “to achieve a better understanding of the past, a better analysis of the present, and a better view of the future.” It would be hard to argue that Congress has come to these terms, but the money it allocated is essential to the humanities across the country.

What appears to have been the golden age of federally funded humanities projects, over 60 years of existence, NEH has paid around $6.5 billion. This averages around $100 million a year over three generations. The majority of that fund is split with grants of less than $50,000, with more than half of that funding flowing directly to individual state humanities councils.

NEH’s fundraising was a very successful investment in the cultural fabric of our country that enriched the lives of countless individuals and strengthened our unions. Some of the projects, such as the publication of presidential papers, go to the heart of the ideas of those who founded the United States and informed generations of scholars. Others have exposed millions of people to live, including creating databases of the Transatlantic slave trade, and have changed how the history of the United States and its people are understood.

My own research on colonial California had a more regional impact. In 1993 I was a graduate student struggling to write a paper on colonial California. Faced with declining support from money, I was fortunate to receive a dissertation fellowship from NEH and allowed my final year to complete my dissertation.

This was one of the first studies in colonial California that was fixed in Spanish sources and the experiences of Indigenous Californians. The fellowship gave me a chance, and in a book in which the paper was funded by neh, I argued that California had a colonial history that was excluded from the narrative of our nation on the grounds of “chronology, geography, and horology.” While it may have been a few words in the book’s introduction, that one statement and book it introduced was an early call that led colonial American historians to work collectively across Virginia and Massachusetts towards a more relatively continental vision of America today.

In the early 2000s, I worked with the Huntington Library’s research department to secure a large NEH grant and helped to create an online database for all people (indigenous people, soldiers, settlers, missionaries) who had been affiliated with the California mission before 1850. village. In real life-changing ways, the NEH-funded database helps people today understand who they are, where they come from, and how they fit into modern California.

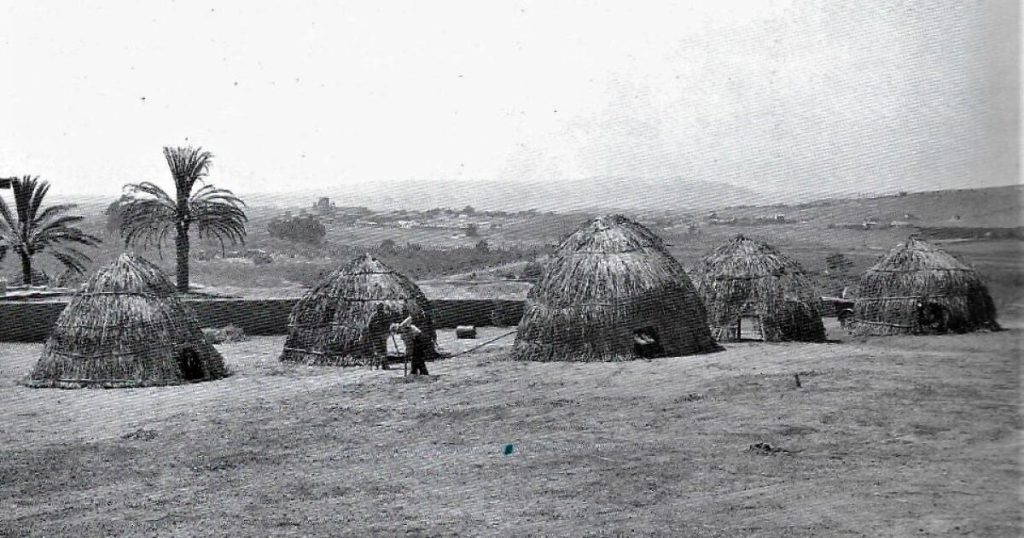

In the 2010s, once again supported by NEH, I worked with a team of researchers to create a visualization of Indigenous movements into the California Mission, which has been featured in museums in Southern California, where we can see how California has been transformed by Spanish colonization.

And in 2022 I received a Neh-Supported Grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which allows for the creation and installation of a new gallery exhibition at Mission San Gabriel, centers on the history of missions on native experiences, and helps to decolorize the collection by seducing native voices and native practitioners into the curatorial process. Visited by 1,000 people a month, the exhibit helps Southern Californians understand their place in the world.

These projects in my mind are just a few of NEH’s contributions to the cultural fabrics of Southern California.

In 2024, NEH funding was about $200,000,000, or 0.0029% of the federal budget of $6.8 trillion. The savings of zero donations are trivial, but the losses to our society today and future generations are immeasurable. When every day is singled out for constitutional order, the economy and structure of our society, education and science, due to budget cuts and ideological conformity, more than ever, we need a robust humanities department to understand the country’s motto and strive to work together with “from many.”

With the legislation of Congress creating the National Fund for the Humanities being clarified, the federal government has “has a “necessary and appropriate” role in promoting humanitarian investigation, not only to create and maintain a climate that promotes freedom of thinking, imagination and investigation, but also material conditions. A wise word that is worthy of attention back then and now.

Steven W. Hackel, chairman of the UC Riverside history department, is the author of another book, Junipero Serra: The Founding Father of California.

[ad_2]Source link