[ad_1]

Today, 100 years ago, downtown Santa Barbara was devastated by an earthquake offshore.

The main commercial district, State Street, was in abandoned. Some buildings have completely collapsed. The vulnerability of that design was exposed by the power of Mother Nature. About 12 people have died.

But despite the destruction, the great Santa Barbara earthquake remains relatively ambiguous, even in states notorious for its tremors, seismically speaking.

There are several reasons, ranging from relatively low deaths to coordinated efforts by modern citizen boosters and business interests to downplay the extent of damage.

But in a state where the next “big thing” is always an attractive threat, the lessons learned from Santa Barbara’s trembling should still resonate – even 100 years from now, experts say.

For example, structural engineers have long thought that brick buildings are one of the most deadly types of structures in earthquakes. And the joy of Santa Barbara revealed how dangerous the brick buildings built in that era are.

But for decades, it was hardly done to force brick buildings around California. From the 1933 Long Beach earthquake to the 2003 San Simeon earthquake, it had fatal results.

After the 2003 San Simeon earthquake, rescuers sifted through pieces of Pasolo Bulls.

(Los Angeles Times)

One of the biggest lessons, according to Jones, is, “We’ve always been the bare minimum because we’re afraid to tell people what to do with our property.” That’s why the building managed to go without critical earthquake modifications over a century before the brick walls fell in 2003.

Many cities ultimately took action to address these vulnerabilities through mandatory modification ordinances, including Los Angeles in 1981, Santa Barbara in 1990, and San Francisco in 1992.

During the magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake, partially collapsed brick buildings in San Francisco crushed the crushed cars.

(CE Meyer/US Geological Survey)

However, other Southern California cities have not acted to demand that undeniable brick buildings be fixed or demolished.

Many cities also have no effect on requiring renovations of other types of potentially vulnerable buildings, including those with certain defects in concrete and steel frames.

Santa Barbara, for example, does not have a law requiring a flimsy first-floor apartment to be earthquake-renovated. These “soft stories” buildings, well-known for their vulnerabilities, are targets of essential remodeling methods in cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Soft Story apartments could collapse. This is because the thin pole holding the carport can snap when it sways.

(Raoul Rañoa / Los Angeles Times)

“I know what’s been said in Santa Barbara, but nothing’s happening,” said Structural Engineer Sage Shingle, a member of ASSN, structural engineer. Principal of Southern California and T&S Structure. Do not request the strengthening of these buildings. “Of course, it makes Santa Barbara more vulnerable than it could,” he said.

A century ago, Santa Barbara also caused great damage to single-family homes, sliding down the foundations with braces and bolts. This is a structural flaw that still exists in many homeowners today. (The state programme solves the problem by providing grants to seduce homeowners.)

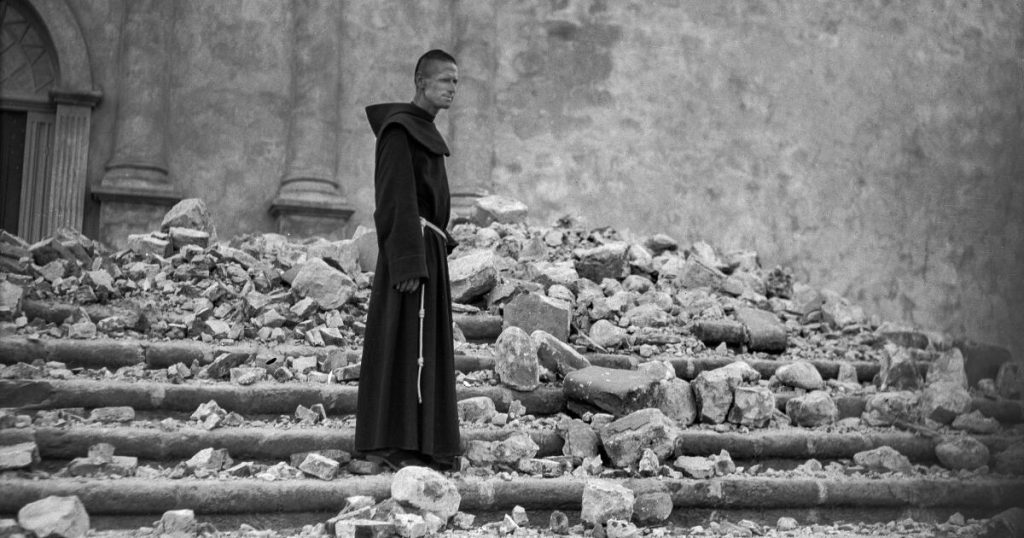

However, the most vivid damage from the 1925 earthquake was the collapse of bricks and stones along State Avenue in Santa Barbara.

After the Santa Barbara earthquake on June 29, 1925, the California hotel was severely damaged.

(UCLA’s Los Angeles Times Archives)

The Californian, a four-storey hotel that opened about a week before the earthquake, saw the brick wall outside it “stripped off the wooden floor.”

In Santa Barbara, architect Greg Retch, president of the Santa Barbara Building Foundation, said “there were a few places to collapse on the sidewalk.”

California learned the dangers of brick construction when a major earthquake struck Long Beach in 1933.

The historic Arlington Hotel was also severely damaged by the 1925 earthquake. It opened in 1911 to replace its burnt-out predecessor in 1909 and was rebuilt in aquariums as a storage for future firefighting activities, Single said. But when the earthquake shaking hit the weight of the tank, “the chunks pulled the building right there, causing that area of the building to collapse,” Single said. Two hotel guests have died.

A century ago, earthquake science was still in its early stages. It may be hard to imagine today, but before 1925 there was “discussion about how serious earthquake risks were in Southern California and Los Angeles, particularly in Los Angeles,” said Susan Huff, a seismologist at the US Geological Survey.

“There were two camps, one claimed there was a major earthquake risk in the Los Angeles area, and another claimed there was an earthquake, but only moderates were the danger,” Huff said.

The Arlington Hotel, the victims of the Santa Barbara earthquake on June 29, 1925.

(UCLA’s Los Angeles Times Archives)

The 1925 earthquake did not resolve the debate, Huff said. Santa Barbara’s fierce competition, estimated to be between magnitudes 6.5 and 6.8, was the same year as an earthquake in Quebec, Canada. It is currently estimated to have a magnitude of 6.2. However, Quebec’s earthquake range covers a wider area. This is because eastern North America rocks are older and seismic waves can move more effectively than in California.

However, at the time, due to the small geographical extent of shaking around Santa Barbara, it was possible to argue that earthquakes were essentially a greater problem for Quebec than for Southern California. The argument said, “Yeah, you have an earthquake in California, but the effect isn’t that wide,” Huff said.

“In terms of public awareness and risk reduction, 1925 didn’t move as much as moving the needle,” Huff said.

Additionally, “There was an effort by business interests to downplay the danger,” Huff said. “There was the idea that there was nothing to gain from scaring people.”

By 1906, the San Francisco Bay area was recognized as having a high earthquake risk, but some views in the Los Angeles area were different. The 1920 Englewood earthquake – estimated at magnitude 4.9 with the epicenter of Santa Monica Bay – was given to seismic minimise on another occasion suggesting that a medium earthquake in the local fault causes the greatest local damage.

“The senses are, ‘Yeah, we have an earthquake. They’re annoying, but they don’t do anything about it,” Huff said. “They mapped faults in the LA area, but they insisted they were not active.”

And, scientists have yet to develop the theory of plate tectonics, explaining why California is particularly vulnerable to earthquakes.

Still, it wasn’t like everyone was completely denial of danger. According to the USGS, people were aware of the risks of a 1923 magnitude 8 earthquake and fire that caused the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and 1923 magnitude 8 earthquake and fire that caused an astounding 142,800 deaths.

At the first moment after the 1925 earthquake, “we had three men who turned off gas, water and electricity. So we didn’t have a fire,” said Santa Barbara historian Betsy J. Green.

The earthquake urged Santa Barbara to adopt a code cited earthquake safety related to the construction of new buildings, originally ordered by local governments in California, according to the Stanford University Blume Earthquake Engineering Center.

A California geological survey found that more actions took place after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, destroying 70 schools, and 120 deaths and shocking Californians after the destruction of 120 people, according to California geological surveys.

Earthquake safety standards were required at state sites in newly constructed public schools. The State Riley Act, passed in 1933, also required local governments in California to establish a building department and inspect new constructions.

However, according to the university, it took until the 1960s before the code for new California buildings became more uniform among local governments.

As a critical moment in Santa Barbara’s history, the earthquake also provided the opportunity to reconstruct its appearance. Even before the earthquake, urban reformers promoted a consistent Spanish colonial revival architecture style used throughout the city. There are many arches. And the roof is generally red tile, with plenty of trim above the windows, and the doors are calm, blue-green colours, said green.

A wealthy resident, Bernhard Hoffmann, not only bought and restored the historic Adobe Casa de la Guerra Downtown, but also bought property next to it and built a store called El Paseo.

Santa Barbara Court in 2019.

(Riccardo Deatanja/Los Angeles Times)

“The idea was that they were trying to make a Spanish street… Santa Barbara was even a tourist town at the time. They really knew they needed to differentiate themselves from Los Angeles and San Francisco, which have a lot of Victorian architecture,” Rech said.

The local city hall was also built in this style, similar to the high school, Rech said.

A earthquake then broke out, and authorities decided to make the Spanish colonial revival style mandatory in the downtown area. Today, some may grouse about the rules. “But it keeps Santa Barbara looking like Santa Barbara, not Ventura or Goleta,” Green said.

(However, this effort had the effect of banishing the city’s old Chinatown, according to the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation.)

The earthquake also seriously destroyed the old Greek revival-style courts of the city, built in the late 1800s, breaking lines and ruining parts of the prison. The county has approved a Spanish colonial revival style alternative funded by bonds in a cost overrun paid by taxes on oil extraction in the county.

View from the clocktower at Santa Barbara County Courthouse.

(Riccardo Deatanja/Los Angeles Times)

The court is now considered one of the most picturesque places to marry in a building in California’s municipal county.

According to Green, a key aspect of Santa Barbara’s recovery was that even a century ago it had developed as a tourist spot for the wealthy, and there were many powerful and influential people who helped send capital and loans for reconstruction efforts.

“There was a lot of money here,” Green said.

[ad_2]Source link