[ad_1]

“Hey man, are you good?”

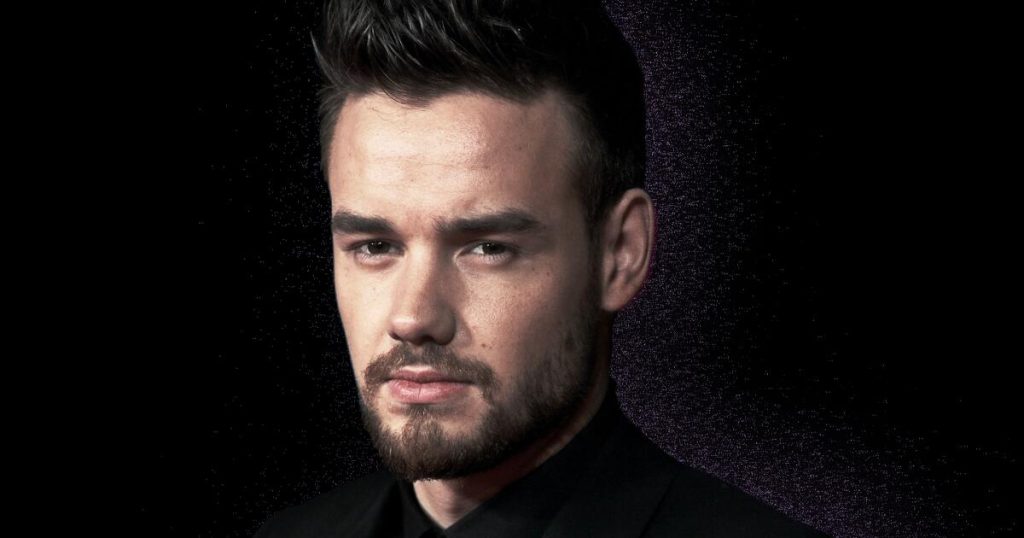

AJ McLean had reason to be concerned about Liam Payne. Since production wrapped on the new Netflix music competition series where they’d met earlier this year, the Backstreet Boys veteran and One Direction star had talked almost every day on WhatsApp — at least until Payne’s sudden two-week silence early last month.

Plus, McLean, 46, knew Payne, 31, had struggled with addiction. On the set of “Building the Band,” where Payne was a celebrity mentor to contestants and McLean the host — the two forged an unusually tight bond over their shared experience: starting their careers in the crucible of teen celebrity and later battling substance abuse.

“He was an absolute light, such an old soul,” McLean told The Times this week, describing the “very older brother” feeling he developed for Payne. “But you could tell you were talking to someone who had seen some s—, who had not lived a normal life.”

McLean, who had his three-year sober anniversary in September, said he did not believe Payne was using drugs during the period when the Netflix program filmed. He said they often spoke “candidly about sobriety, sharing stories and one-upping each other. We could laugh about it all, because if you’re still there to talk about it, that means you’re moving in a good direction.”

As it turned out, though, Payne was again fighting his demons. On Oct. 16, one day after McLean texted his final check-in, the singer fell to his death from a third-floor hotel balcony. Authorities found Payne’s Buenos Aires hotel room strewn with drug paraphernalia, and an autopsy showed “pink cocaine,” a mix of designer drugs, in his bloodstream.

The pop star’s shocking death placed a tragic spotlight on the ups and downs of the One Direction member who struggled most acutely to chart a post-boy-band course, and renewed age-old questions about how to support troubled young artists caught in the crucible of modern fame — as well as hold them accountable.

“I feel like there will never be a definitive answer as to why this happened. That’s the most painful thing to sit with. Why now? Why this way?” McLean said. “But there’s no rhyme or reason when you’re hurting and looking for escape.

“I can torture my brain about ‘Why didn’t he respond?’ But I get it. I just hope people remember him the way he was — a massive heart and a massive talent.”

A photo of Payne nestled among flowers and other tribute items at a memorial for the late singer in Argentina.

(Natacha Pisarenko / Associated Press)

In 2008, 14-year-old schoolboy Liam Payne confidently strode onto the audition stage of the U.K. singing competition “The X Factor.” Sporting the era’s ubiquitous sideswept bangs, he told the judges: “I’m here to win.”

With a rendition of Frank Sinatra’s jaunty “Fly Me to the Moon,” Payne showed off his immaculate pitch and rich vocal tone, and a rakish presence beyond his years.

“I think there is potential with you, Liam,” said judge Simon Cowell. “I’m just missing a bit of grit, a bit of emotion.”

While fellow panelist Cheryl Cole — the Girls Aloud member and future mother of Payne’s son, Bear — seemed charmed, Cowell was less certain about Payne’s solo star power. “You’re a young guy, good-looking, people will like you,” Cowell said. “But there’s 20% missing from you.”

Payne was axed from the show but, undaunted, returned to audition again two years later. It was during that 2010 stint on “The X Factor” that Cowell anointed him a member of One Direction, which would go on to become one of the most successful pop groups of the decade.

But Cowell’s initial concern over Payne’s prospects as a solo artist presaged a challenge for the young star as he sought to fashion a musical identity separate from his One Direction mega-fame. After the band split in 2016, a handful of its members quickly found popularity on their own — most notably Harry Styles, who has since won three Grammys and had the sixth-highest-grossing concert tour of all time. Payne, a gifted lyricist and voracious listener, had a steeper climb to find his own sound.

Payne, pictured while performing in London in 2012, was chosen for One Direction after his second audition for U.K. talent show “The X Factor” in 2010.

(Joseph Okpako / FilmMagic)

In One Direction, it was often Payne, born to a working-class family in Wolverhampton, England, who held the group together. The other members even referred to him as “Daddy Direction.” “When something was going wrong, I’d get a phone call. If there was an apology needed, it was me,” he recalled in 2017. “I was the spokesperson for the band, as it were, with the press and the label.”

He was no slouch musically, either. Payne could virtuosically ad-lib live through the bridge of “Summer Love” or hit piercing high notes on a cover of Michael Jackson’s “The Way You Make Me Feel.” He got more lighthearted as the band settled in, tussling with Louis Tomlinson in onstage water fights and deadpanning in a banana costume on a European tour.

As a writer, he showed a distinct wit and emotional insight, and he grew into one of the band’s most prolific pens — the collaged pop-lyric conceit of “Better Than Words” was his idea.

Yet on “Story of My Life,” one of the band’s beloved cuts, he took the most wrenching lyrics for himself: “It seems to me that when I die these words will be written on my stone. … Although I am broken, my heart is untamed still.”

“I had no idea until we spoke about his music that he was such a driving force lyrically,” McLean said. “When five individuals are put together in a group, the machine generally says, ‘You’re the pretty faces, sing. We’ve got the writers and producers to make this album the biggest thing.’”

Although he may have felt at home writing music, Payne said he found it difficult to adapt to the intense attention that came with being in 1D. As a child, he’d been diagnosed with a scarred kidney — a condition that left him fearful of drinking. But when doctors said he could imbibe at 19, “The floodgates opened,” he recalled in 2017. After performing for thousands of fans, he said, the band often would be confined to their hotel rooms, lest they be mobbed on the streets. And “the minibar is always there,” Payne said.

“I wasn’t happy. I went through a real drinking stage, and sometimes you take things too far,” he elaborated. “Everyone’s been that guy at the party where you’re the only one having fun, and there were points when that was me.”

But Tom Krueger, who spent a month with the band while working as a director of photography on 2013’s “One Direction: This Is Us” documentary, said Payne kept any struggles under the surface.

“Some of them were more standoffish, but Liam always was fun-loving and approachable,” the cinematographer told The Times. “He was pretty sensitive and empathetic. I would look at him and he would look at me and I wasn’t just a face in the mob — I was a person too.”

One Direction members Harry Styles, left, Liam Payne, Louis Tomlinson, Zayn Malik and Niall Horan at an event to promote their 2013 film “One Direction: This Is US.”

(Koji Sasahara / Associated Press)

Yet at the time, Styles was “the Mick Jagger of the bunch — he had this incredible confidence that whatever happened, he was gonna be on top,” Krueger said. “And some of the others, I felt like they kind of lived in the shadow of that.”

When One Direction went on indefinite hiatus in 2016, Payne looked to reframe his roles as both writer and pop star. He cut some EDM remixes as “Big Payno” and signed to Republic (and later Capitol) as a solo act. He wrote in the One Direction book “Who We Are” that he was “worried about the idea of failing outside of this band,” and said he imagined a career in songwriting because “there would be less attention on my life.”

Without his 1D brethren, though, Payne felt less sure of himself than he’d anticipated. He started going to therapy because he “couldn’t really figure out what was making [him] sad,” he said in 2019. The analyst asked him what he liked to do. “I don’t know what I like doing!” he replied.

“I remember standing in my garden at my house and just looking around thinking, ‘It’s been a lot of fun, but what do I do now that’s done?’” he recalled. “‘What actually happens at this point? Who do I call?’”

His loneliness “nearly killed him,” he said, acknowledging that he came close to acting on his suicidal ideation: “It was very touch and go at times.”

For a time, Payne found the connection he was missing in his love life. Eight years after auditioning for her as a 14-year-old on “The X Factor,” he began dating Cheryl Cole, a decade his senior, and spoke glowingly about her to the press, recounting how he watched her perform as a kid.

“Now we’re together with a kid,” he gushed in 2017, six months after the birth of the couple’s first child, a boy named Bear. “I feel like I’m ‘X Factor’s’ biggest winner.”

Payne with his partner, former Girls Aloud member and “X Factor” judge Cheryl Cole, with whom he shared a son, Bear.

(Francois Mori / AP)

Their relationship, which lasted two years, was a fixture in the U.K. tabloids. “The funniest thing was, a week before we were getting married. The next week we’re splitting up,” Payne said in 2018 of the headlines. “I just like to think we’re somewhere in the middle. You know, we have our struggles — like of course I’m not gonna sit here and say that everything’s absolutely fine and dandy, because of course you go through different things, and that’s what a relationship is.”

Payne also had recently made his first serious commitment to sobriety. In 2017, he began a two-year professional relationship with Chip Somers, a psychotherapist and sober companion who had been “put forward as somebody who could deal with people with notoriety and could be trusted to do so.”

“There was a great deal of pressure to keep it private, and quite rightly so,” Somers told The Times. “I don’t believe that anybody should put themselves into a position of pressure in the first year of their sobriety.”

Somers spent almost every day with Payne, he said, and once the performer got clean, “He loved it. Like everybody, he came alive. He had fun. He found a genuine ability to just have a laugh.” The therapist said Payne found joy in simple activities, like playing TopGolf or going 10-pin bowling. When their work together came to an end, Somers was hopeful about Payne’s sobriety.

In the following years, as he learned about Payne’s ongoing struggles, Somers said he sent the occasional text to his former client. But he didn’t want to push too hard. “When people know where help is available, they know the people they can ring or contact to get help. Really, you have to leave it up to them,” he said. “And I think it’s inappropriate to start what would almost be cashing in on their relapse.”

In 2019, Payne became the last of his 1D bandmates to release a solo single. “Strip That Down,” a bouncy Neptunes- and Justin Timberlake-style tune co-written with Ed Sheeran and featuring rapper Quavo, was a moderate hit, reaching No. 10 on the Billboard Hot 100. But it was striking for how overtly it separated him from the band. “You know I used to be in 1D, now I’m out free,” he sang. “People want me for one thing, that’s not me.”

Payne performing in 2017.

(Taylor Hill / FilmMagic)

“Strip That Down” would turn out to be his only top-10 solo single, and just three other tracks cracked the Hot 100. His 2019 debut, “LP1,” peaked at No. 111 and spent only one week on the album charts. Payne’s voice — so flexible and powerful within One Direction’s group dynamic — was more adrift as a solo act. “‘I had a bit of a problem formulating what was going on in my brain into the music at first,” he said then.

A music video director who worked with Payne during this period told The Times that he had in-depth discussions with the singer’s team, but realized upon meeting Payne the day prior to filming that “he had no clue what we were going to be doing. It was clear his team hadn’t involved him in any conversations,” said the director, who requested anonymity because he still works in the industry.

The director also was told to make the video sexier to align with a new ad campaign Payne had signed onto. “It felt like there was this persona being pushed on him, and I couldn’t get a sense for who he was,” the director said. “But I did feel this sadness coming from him — kind of like a helplessness.”

Former Payne managers Richard Griffiths, Simon Oliveira and Steve Finan O’Connor did not respond to The Times’ requests for comment.

Payne was still feeling the aftershocks of life under the 1D microscope as well. He developed agoraphobia, describing in 2019 how anxious he got leaving the house to order a coffee at a nearby Starbucks.

“I even used to have a really bad problem with going to petrol stations and paying for petrol,” he said. “I can feel it now — it was like this horrible anxiety where I’d be sweating buckets in the car, thinking, ‘I don’t want to do this.’”

He’d experimented with bouts of sobriety, going one year post-1D where his only “vice was cigarettes,” and attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, one time with Russell Brand.

But Payne was paranoid that anything he shared would be leaked to the tabloids, and he disliked how his “social life plummeted” when he was sober. He’d wake up early to go running and be in bed by 7 p.m., he recalled. “And in a strange way I am trying to still figure all that out and get the balance right.”

In 2019, he said, “Sometimes it doesn’t matter if you do make a mistake or the night does go a little too far. As long as I can get my job done the next day at a capable level I’m happy with, I can just write that one off as a lesson and go, ‘I won’t do that again.’ I still like to go out and enjoy myself.”

For highly scrutinized boy-band stars like Payne, “There’s a long history of being devalued except for the money you can make for someone. It’s very easy to develop an addiction to get through the day,” said Allison McCracken, a scholar at DePaul University who studies intense pop fandoms. “It’s very difficult to stop when your sense of self-worth is tied up in what made you a star. If you don’t have a strong support group to say, ‘This is a problem,’ and that other things about you are worthwhile too, it’s very difficult to stand up for yourself.”

Payne began dating Maya Henry after his split with Cheryl Cole. Here the pair attend the 2021 BFI London Film Festival.

(Joel C. Ryan / Invision / AP)

Payne was also in the throes of a tumultuous new romance. In September 2019, he began dating Maya Henry, a 19-year-old model who made headlines as a teenager because her quinceañera cost $6 million. Just a few months into their relationship, TMZ posted video of Payne fighting with the staff of a Texas bar near Henry’s home. “I swear to God, I will lay your ass out,” Payne yelled at the bouncers in the clip.

Henry and Payne would later get engaged, but by May 2022, the couple called it quits for good. Payne said their on-and-off again relationship left him feeling “disappointed in myself that I keep on hurting people. That annoys me. I’ve just not been very good at relationships. … I just need to work on myself before I put myself on to somebody else.”

As in the aftermath of his marriage to Cole, romantic problems seemed to create a new personal and professional resolve in Payne. After a few years of one-off collaborative singles, like 2020’s “Midnight” with EDM star Alesso, in 2023 he alluded to a new album in progress. That July, he posted a video on his YouTube page discussing his renewed focus, telling his fans he was six months sober after a 100-day rehab stint.

The new commitment, he said, began while attending a Hans Zimmer concert in Dubai, where he looked at the drink in his hand and thought: “You know what? This isn’t really serving me at all. I don’t really need this right now.”

A few days after his YouTube confessional, he went into more detail on Instagram about the “manic” feelings he was struggling with. Typically, he said, he’d lose his sobriety during those moments, but said he was now under the care of “some amazing people around me that kind of look after me.”

“I’ve filmed this same video about 20 times at different points this year and got too scared to put it out by talking myself out of it,” he said. “I wanna give any of you struggling the gift I was given by sharing some of the things I learned from specialists whilst I was away. … first thing I did every day was check in and it’s important you don’t bottle up how you feel.”

He’d also begun to repair relationships with his old band, appearing at the premiere of Tomlinson’s documentary and applauding Styles’ win for album of the year at the Grammys. ”I’ve suffered a bit of a dark time in my life at the moment. Honestly, I wouldn’t be here without the boys,” he said at Tomlinson’s premiere.

Payne’s final single, “Teardrops,” was released in March 2024. The song showcased his full high vocal range and featured an admission of his failures and vulnerabilities as a partner: “I don’t know how to love you when / I am broken too / Maybe your words make sense / I could be the problem, I’m so sorry.”

Yet behind the scenes, his future as a commercial solo act was uncertain, as Payne had recently split from his label, Capitol Records.

A representative for Universal Music Group and Capitol declined to comment, but sources familiar with the situation said that the label and Payne’s management had disagreements about Payne’s musical direction, and Capitol was concerned about sending Payne on tour, given his recent struggles with substance use. A month before his death, Payne and the label had parted ways.

“We are devastated by the tragic passing of Liam Payne,” Capitol said in a statement posted online. “His legacy will live on through his music and the countless fans he inspired and who adored him. We send our deepest condolences to Liam’s family and loved ones.”

An illustration from Maya Henry’s novel “Looking Forward,” which the author has said was “definitely inspired by true events.”

(Thomas Warming)

In the weeks leading up to his death, Maya Henry had been increasingly vocal online about what she described as a toxic relationship with Payne. The revelations began in May of this year, when Henry published a novel called “Looking Forward,” which she described as “definitely inspired by true events.”

The book follows a model named Mallory who falls for Oliver Smith, a former member of a boy band called 5Forward! Oliver is an addict, alternately abusing alcohol, MDMA, cocaine and prescription pills. At one point, he chases her with an ax. And in one particularly disturbing scene, Oliver gets intoxicated, begins repeatedly hitting himself in the face and rushes toward the balcony sobbing. Mallory pleads with him to come back inside.

“I’m gonna f— kill myself, okay? I want to die,” Oliver says.

In an interview prior to the book’s publication, Henry said she had “rose-colored glasses” during their relationship.

“When you’re in those situations, they kind of become normal to you. These things start happening, and it just becomes normalized in your head,” she says. “I just became so desensitized to everything going on that I was like, ‘OK, this is my relationship, and this is how it’s going to be.’ And I feel like once you get out of [it], you’re really like, ‘Oh my gosh, what was I doing, and why was I there?’”

Through a publicist, Henry declined to comment for this story.

Fans of former One Direction singer Liam Payne gather at the Obelisk to honor him one day after his death at a hotel in Buenos Aires.

(Victor R. Caivano / AP)

The future of Payne’s posthumous music and television work remains uncertain. Payne’s producer Sam Pounds decided to withdraw a planned new single, “Do No Wrong,” after intense fan pushback. “Today I’m deciding to hold ‘Do No Wrong’ and leave those liberties up to all family members. I want all proceeds [to] go to a charity of their choosing (or however they desire),” Pounds wrote. “Even though we all love the song it’s not the time yet. We are all still mourning the passing of Liam and I want the family to morn [sic] in peace and in prayer. We will all wait.”

For now, those close to Payne are trying to make sense of his death, including whether there was more they could have done to intervene — while hoping that his chaotic final days will not wholly define his legacy.

As Somers put it, remembering the “fragile, gentle young man” he’d helped get sober back in 2017: “I think to judge anybody on a night when they are very intoxicated would be a tragic mistake.”

Staff writer Jessica Gelt and researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link