[ad_1]

You’re at the grocery store, reaching on your tiptoes to pick up the milk on the top shelf with the most recent date on it. You think it’s worth it to have milk that stays fresh longer.

Of course, you won’t be able to finish drinking the milk by that day, so you dutifully pour the rest down the drain the next day.

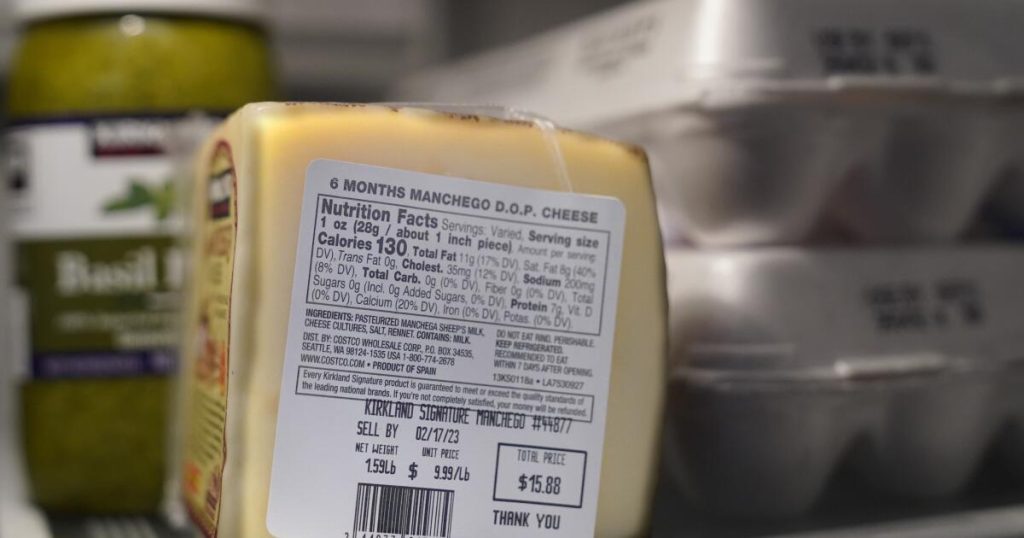

But that “sell by” label doesn’t indicate when milk goes bad, it’s meant to help grocery stores rotate inventory. Your milk was fine. Now, you go back to the store and pay the extra fee.

With the exception of infant formula, date labeling on packaged foods is not federally regulated or required, leaving it up to manufacturers and states to decide what labeling is required. Older state law proposed labeling food with dates so consumers would know when it went bad, instead of confusing “seller” labels for grocery stores. Ta. California’s new law requires Californians to reduce the amount of food waste they produce by 6 million tons each year, according to the state Department of Food and Agriculture.

The goal of Assembly Bill 660, authored by Rep. Jackie Irwin (D-Thousand Oaks), is to bring uniformity and common sense to dated food labels for consumers. To do that, grocery retailers and manufacturers will need to make changes, said Daniel Conway of the California Grocers Association. Vice President of Government Relations.

Between developing a new inventory system, retraining employees, and even determining which labels need to be adjusted, changes won’t happen overnight, Conway said. The law will go into effect on July 1, 2026, giving grocery stores about a year and a half.

“Wondering whether our food still tastes good is something we’ve all struggled with. By strengthening labeling standards and reducing food waste, AB 660 will help the environment and the planet while It will continue to leave money in consumers’ pockets,” Irwin said in a release after the bill passed.

With over 50 different phrases on food packaging, it can be difficult for consumers to understand exactly what each label means. That’s what she hopes the legislation will improve, according to Nina Sevilla, a sustainable food systems advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the bill’s sponsors.

Some labels are acronyms for longer phrases, such as “PEB” for “Enjoy.” It’s a gibberish phrase that Erica Parker, a policy director for bill sponsor Californians Against Waste, said she once saw on a pack of tortillas.

To make matters worse, these 50 phrases are not used consistently across manufacturers. A “best by” label might indicate the best date of quality on one product, but it could mean something else on another, Parker said.

“The ultimate goal of AB 660 is to bring consistency to date labeling practices, thereby reducing consumer confusion and, as a result, food waste. It’s about creating a unified system that allows people to make informed and empowered choices,” Parker said in an email.

The new law bans putting “sell by” labels on food, which could lead to people throwing away food that still tastes good. “Sell by” dates are commonly used in grocery stores to ensure that stocks, especially dairy, meat, and other perishables, are cycled properly, but they do not necessarily indicate when food will go bad. .

Instead, the law limits most labels to two options. One is the quality label, “use by” date, and the other is the safety label, “use by” date.

A “use by” label indicates a date by which the product may be of poor quality, but it does not mean it is not safe to eat. This is especially true for products that don’t deteriorate in stores, such as bottled water or canned products, which, if unopened and properly stored, can be safely consumed for years after the label is applied, according to U.S. Consumers. Department Manager Teresa Murray said. Public interest research group. The organization works to identify and address issues of public concern relating to health, safety and well-being.

Murray said the new law will point California consumers in the right direction, adding that he hopes it will help educate consumers about what these labels actually mean. Anything that helps consumers avoid throwing away edible food is a good thing, she says. Murray recommends the FoodKeeper app developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This app helps users understand food storage and get maximum benefits by avoiding food waste. Available online or as a mobile app on Android and Apple devices.

It could also help nonprofits like food banks accept more non-perishable food, Murray said. Some food banks may throw away or not accept canned goods if the displayed date is close, without considering what the date actually means.

Sevilla said the dates should be used as a guideline. For most foods, he said, consumers should use their eyes and nose to check for unusual colors or odors before throwing them away.

AB 660 requires “if-to-use” safety labels for products that can quickly perish, instead of the quality-oriented “best-to-use” labels. Products that may not be safe to consume after the date printed on the label must be packaged with a ‘use by’ date.

California’s new law is not as strict as other states, such as Pennsylvania’s milk labeling law, which requires a “sell by” date of 17 days after a product is pasteurized. Mr Murray said food spoilage is not as simple as picking a day, but labels should be considered when determining if food is still good or needs to be thrown away.

The new law also allows grocery stores to use “prepackaged” labels on prepared foods, as long as they also include quality and safety labels. State law exempts some products from state labeling requirements, including infant formula, eggs, beer and wine.

[ad_2]Source link