[ad_1]

Tired of having to run through the streets of West Compton in the early 1970s, AC Moses and his childhood friends united to protect the other local gangs that bother them.

They called themselves the Pyros after the small streets they grew up and eventually formed one of the first known blood gangs. But at the time they were more voluntary neighborhood patrols than the muscular crime companies that law enforcement says they will become.

Moses went to “Kingbobaroy” and created his own name as a fearless brawler who could take punches. He and his followers protected each other from flying around on their way in and out of school. Sometimes they crossed over to rival territory with retrieval in mind.

In a 2017 interview with YouTube gang historian Kevin “Kev Mac” McIntosh, Moses said that he and his friends abandoned their class and walked to 1 Centennial High School, and were responsible for attacking his cousin the day before We talked about how we were going to stand up to. Moses bent his score in the evening.

He spotted one of his cousins and chased down the hallway.

“I managed to get through that attack and said, ‘Man, f-it’. And we walked up to Pill Street and got all the other siblings,” Moses said in an interview. Everyone left there. ”

Over time, authorities said Pyros’ brand of violence had escalated beyond street fights to killing, robbery and drug trafficking.

When he was not on the street, Moses pursued his other talents: sing. His husky baritone has had hits for the Philadelphia soul group The Delfonics, including “La la Means I Love You” and “I Dod I (this time blew your mind off).”

“If it wasn’t because of the cigarettes, he would probably still be on tour,” said longtime friend Skip Townsend.

According to his longtime friends, the impact of AC Moses is difficult to measure, especially for outsiders who may not be able to see past his gang legacy.

(Skip Townsend)

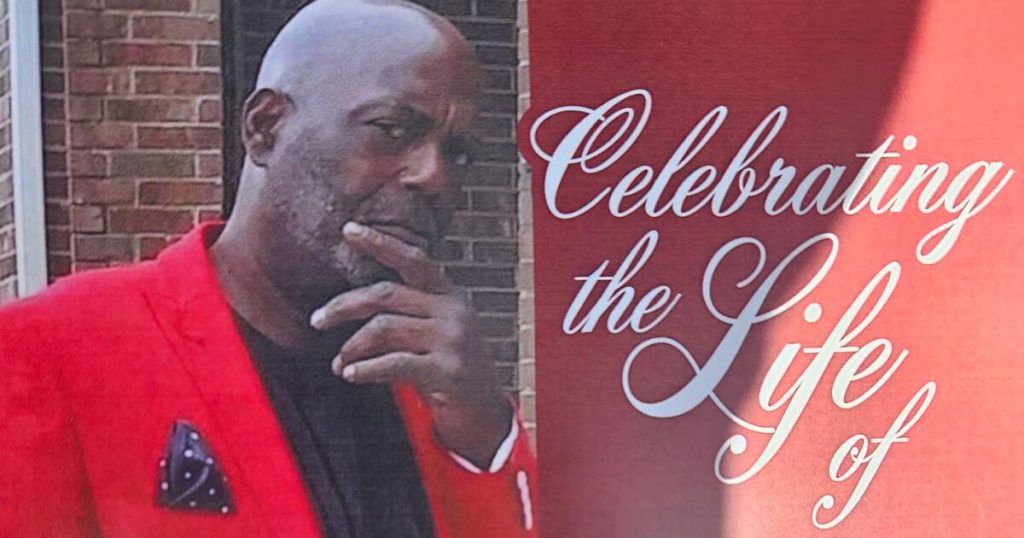

Moses passed away last month at the age of 68, leaving behind eight children and ten grandchildren.

His life dichotomy was on display between hardened gang members and soulful crooners during his occasional service in the county prison system. .

Townsend recalled how he and Moses were trapped in a high-security module designated for young black men labeled blood by law enforcement. When the lights went out at night at 10am, he remembered to continue to wake up to see if Moses would play the show.

“Everyone will be quiet and say, ‘OK, Boba, I’ll sing for us,'” Townsend said.

Her sister Sandra remembers one of his shows at Delfonics during a stop on the group’s reunion tour at The Proud Bird, an aviation-themed restaurant near Los Angeles International Airport.

She was well versed in his gang exploits, but she said she had seen another aspect of Moses in full. To her, he has always been “AC.” The family baby was hopelessly restrained by her mother after a temporary loss of ability to speak after surgery as a child.

Growing up, she said, he loved to make claims, always wanting to share his point, but he wanted to hear the other side.

The two bonded together in a shared love for music, and sometimes even plunged into singing together, both at home and in public. Their go-to duet was a slow jam for “Always and and Forever,” originally performed by Heat Wave. Moses also took his mother and his aunt with love for cooking, she said. His specialty was fried chicken gizard.

Sandra often acted as a guardian, intervening to protect him from her mother’s rage and misleading police officers who had been searching for him. However, she showed him a harsh love. One day she remembers he slammed at the back door of their house and begging them to let them in to escape the children in the neighborhood who wanted to fight him. She didn’t latch the lock by saying he needed to head to them.

“He made sure he didn’t run away from that fight,” she recalls. “And from that day on, they didn’t ruin the AC.”

Trouble seemed to find him, she said – because he is responsible for stirring it. Once, at age 17, he and his friends “hijacked” the city bus and forced the driver to turn around and return to the beach.

By the time he reached his 30s, his rap sheet included a conviction for robbery and possession of drugs. His sister tried to distance herself when his family became a gang.

“He didn’t recognize them as bad influence or something that held him down,” she recalled. In later years he suffered from substance abuse.

Early black gangs, which began amid the racial turmoil of the 1950s and 60s, saw the names of macho names like Gladiator and Slauson, according to Patrick Lopez Aguad, an associate professor of sociology at Santa Clara University. He was a loose, organized crew. We studied gang identity. They coexisted relatively peacefully, claiming to many black neighbours, he said.

Most people were soaked up in the rhetoric of “empowerment, self-sufficiency” and community-controlled Black Panthers. He states:

Shooting and murder were far less common. The gangs at the time united to prevent police harassment, “to fight against either the black neighborhood or the white children who come to their subpoena, and open isolated spaces in the city, like pools and parks. I was fighting,” Lopez Aguado said.

The professor said the group committed a crime, but their crimes were relatively detailed by today’s standards. Brawls and shakedowns of non-gang members for their bikes and lunch.

That changed in the 1980s. Cheap crack cocaine began to flow into rising and inflation in Southern L.A., combined with the closure of federal programs that provided lifelines to the poor and encouraged an explosion of local drug trafficking. Violence has become more regular and indiscriminate. As the city’s murder rates skyrocketed, Blood and Crips and its affiliates acquired the national prestigious.

Gradually, a new set of pyrus began to sprout. Like them, the influence of OGs like Moses has faded. The county’s juvenile camp has become a fertile training and recruitment venue. Over the years, gangs have grown and forked into countless “sets” in Southern California and elsewhere in the country, and signaling loyalty by wearing hats from sports teams like the Philadelphia Phillies and the Washington Nationals. Masu. Grammy-nominated rapper The game is one of those claiming membership.

Born in Houston in February 1956, Arthur Charles Moses moved with his mother and siblings at a young age.

Moses self-published the book The Starting Lineup. He calmly looked at the origins of both Crip and Piru gangs and explained how their allies once became bitter rivals.

The book follows his family’s journey from Texas to Los Angeles in the late 1950s, in the footsteps of millions of African Americans who fled Jim Crow South to the North and West Promise .

Moses moved to Watts with her grandmother. His parents ran a dry cleaning business on the corner of Manchester Avenue. The family then settled near 77th Avenue and Broadway, where he first felt the tug of war in gang life.

In a recent podcast interview he recalled how he was drawn to older members of the local avenue gang. However, Moses was said to be too young for him to participate.

He then collapsed at Mary McClure Bethune Middle School with a group of children, including Raymond Washington. Raymond Washington formed the clip alongside another Southern LA native Stanley “Tekui” Williams. Washington was killed in a shootout in 1979. Williams was executed by the state of California in late 2005.

To escape violence in the area, relatives say Moses moved with her aunt and her family at her West Pill Street home.

He roamed the streets with his cousins Ralph and Terry. He was killed decades later when he ran to the car driven by former rap Impreza Rio Marion “Suge” Knight outside the popular Compton Burger Joint. Knight was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the case and was sentenced to 28 years in prison.

After falling alongside his former companion clip, Moses and the other Pilas first called the Pill Street boy – along with several other Area Street crews, as known as Blood I participated in what I mean.

As Moses explained in an interview a few years later, division became respected. “You’re pushed away and told me what to do and you want your own strength,” he said.

Moses may be ruled out of gang origins, such as Sylvester “Puddin”, Vincent Owens, and Lorenzo “LB” Benton, where Moses considers important influences. Another early pill leader, Larry “Tam” Watts, was shot in a 1975 drive-by shooting.

But the name “Kingbo Valoi” still weighs among people old enough to remember back then, saying that gangster historian Alex Alonso, who worked as a professor at the California State University System. said.

“He was a first generation member of Crips, he was a first generation member of Pyros, and he ended up in blood. At the time, they were not in conflict. But today, It sounds crazy like, “Was he clipped and blood?” ” Alonso said. “So he probably has one of the most unique and historical perspectives that everyone has to offer.”

In recent years, Moses has been interviewed on Alonso’s street television and other YouTube channels dedicated to the lore and history of Lagang, and has occasionally been caught up in a heated debate about Pilas’ origins.

Townsend, a gang interventionist, agrees that “Bobaloy should be credited.” Townsend was in the Red and Burgundy waters of hundreds of mourners who attended Moses’ funeral at Angelus Funeral Home earlier this month.

Today, Townsend says Moses’ influence is difficult to measure, especially for outsiders who may not be able to see past the legacy of the gang.

“He actually united us,” he said. “Of course someone on the West Side is going to say, ‘Yeah, he’s just a bloody gang member.” ”

[ad_2]Source link