[ad_1]

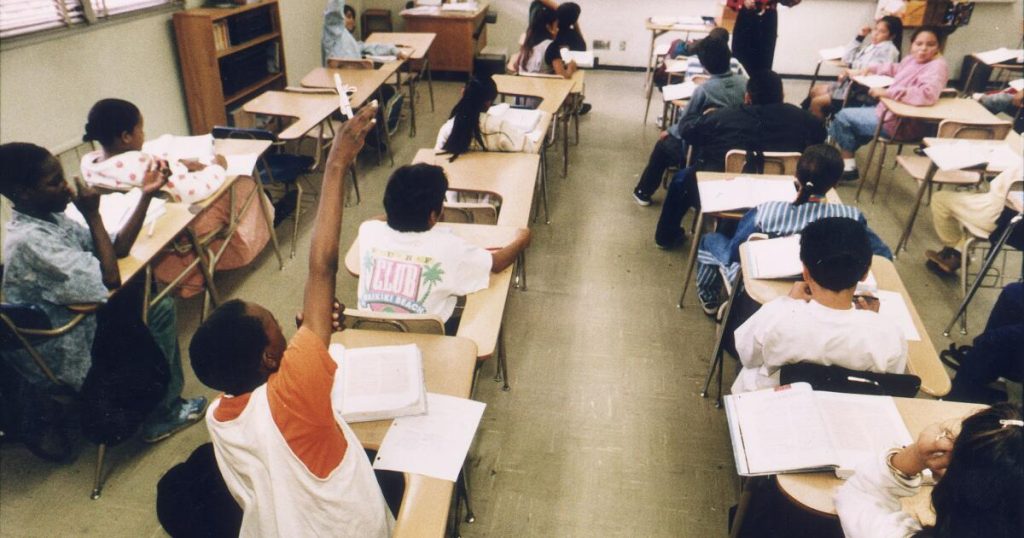

Schools generally work hard to meet the special educational needs of a variety of students, including students with learning disabilities, students learning English, students with behavioral problems, and students from families living in poverty. I have been working on this. But they have widely ignored one major group of students with special needs: academically capable students.

Many school districts across the country have eliminated programs for students who are up to speed. The trend to eliminate or reduce such programs began about 15 years ago. But the Black Lives Matter movement has forced schools to consider the perplexing fact that blacks and Latinos are far less likely to be recognized as gifted than whites or Asian students. In 2021, this trend gained momentum.

Part of the problem was that the original purpose of gifted programs was lost in parents’ competition for prestige and dominance. Unlike other special education categories, the gifted label was coveted by parents. Classes, and sometimes entire schools, for gifted students often had a richer curriculum and more resources. They became classrooms for high achievers rather than classrooms for students appropriately defined as gifted.

These programs were originally intended to meet the needs of students with intensive and irregular learning patterns. They were often considered so good that they did not require special attention. Because standardized tests required schools to target student proficiency, attention focused on students who did not meet those standards. Those who exceeded that were considered OK.

But they’re not just energetic. Gifted children tend to shine in certain areas and struggle in others compared to other children, a phenomenon known as asynchronous development. A 3rd grader’s reading comprehension is at an 11th grade level, but their social skills may be closer to that of a kindergartener. They often find it difficult to connect with other children. Additionally, students are at risk of being withdrawn from school due to slow progress in classes.

I don’t know if I was recognized as gifted when I was a kid, but I was definitely bored when I was in elementary school. Everything felt like it was repeated until it was pointless to pay attention to the lessons. I started doing things just to keep myself occupied.

My third grade teacher tried several strategies, including sending me on an errand that she devised to get me out of the classroom. Nothing worked. So they promoted me to fourth grade even though school policy prohibited it.

It was a disaster. I became estranged from my friends and felt anxious about being constantly questioned by adults and children about why I was in the upper grades. I wasn’t doing well academically either. I enjoyed the challenge of catching up, but once that happened, school became boring again. The problem was not with the third-grade material. It was a learning pace.

When I started covering education in the late 1970s, it was a pleasant surprise to see this need addressed. However, it was a little jarring to hear a 10-year-old refer to himself as an “intellectually gifted minor” at school. Board meeting. “MGM” was the name given to the program, which was later renamed “GATE,” which stands for Gifted and Talented Education.

However, it was never clear what exactly gifted education was. In some school districts, it was a popular school for high-achieving students. Sometimes it was enriching for certain students. Like teachers with special education, teachers were supposed to have special training, but it seemed to be hit or miss. At the school my kids attended, gifted programs basically meant extra homework.

When talent becomes a matter of honor rather than a particular learning style or need, all bets are off. Perhaps the problem is that you called it “gifted” instead of “asynchronous development.” No one would fight to get their child into an asynchronous development program unless they had to.

There is little doubt that racism played a role in identifying children as gifted, even if the labels were based on supposedly objective criteria. But the solution to this problem lies in eliminating bias, not in the program itself.

To its credit, the Los Angeles Unified School District has maintained gifted education by offering programs for a variety of academic and creative abilities. One is for highly gifted students who are fully exposed to college content in some areas while still in their sophomore year of high school. However, because students of color are enrolling proportionally fewer students, the district recently relaxed admission requirements before reversing policy. The criteria should be very simple. It’s about the need and ability of students to move through academic content very quickly.

California does not require schools to offer gifted programs and stopped funding gifted programs in 2013, so schools have little incentive to maintain gifted programs. Certainly, the answer is not to eliminate the program completely. Exposing it to all children didn’t seem to have any effect. This has caused some to slow down and become less purposeful.

Differentiated instruction, where teachers tailor lessons to the different needs of their students, sounds good but is difficult to implement in large classes.

My older child was fortunate to be able to participate in a small public school program that was open to all until space was filled, and many of the problems of differentiation were resolved. It involved some testing and many separate projects. Students chose a book to read and report on themselves. Their project could be writing a report, or if they have other talents, it could be a movie, a play, a song, a board game, etc. As long as you show that you have learned the lesson at hand. This gave students the freedom to work at their own level, avoid boredom, and show off their talents.

However, the program was run by two extremely talented teachers who knew how to bring out the best in each student. It’s much easier to grade tests than it is to evaluate projects, but you never know how replicable a program will be. In any case, it no longer exists.

[ad_2]Source link