[ad_1]

Did she scream? Was it noisy enough? Has her dress torn enough to prove she fought?

These were some of the questions that 17-year-old Lana Soyer faced in one of America’s first rape trials in 1793.

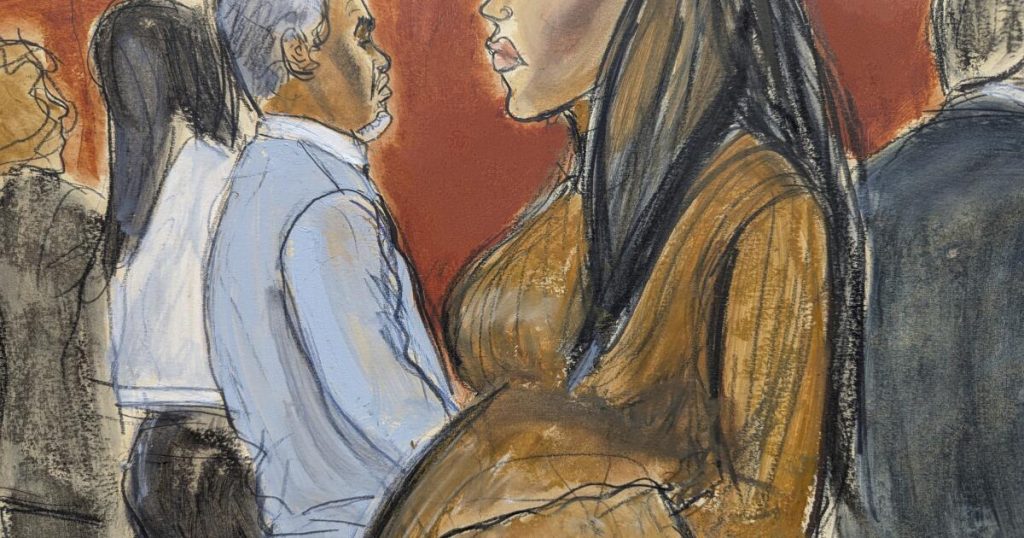

With the fourth week ending with Sean “Diddy” Comb’s sex trafficking and assault trial, it’s becoming more depressingly clear that the more things change, the more things remain the same, especially when it comes to how survivors of sexual violence are treated. Despite almost a decade of the #MeToo movement, the woman who testifies against the comb is on trial as much as he is, and Sawyer is on trial as much as 232 years ago.

Why didn’t they leave? Why did they texted out didi-friendly notes? Isn’t this all about cash conversion?

Again, women are asked to explain not only what happened to them, but why they responded the way they did. It is our collective, ongoing need to police and scrutinize how women respond to trauma.

For many people, there is the right way to respond to sexual violence – crying, ggling, pleading, running, fighting, yelling, and reporting to the police immediately. If women do not fit these narrow, male approval responses, well, they must be lying – or willing.

When appropriate, Bill Maher’s recent uneasy rant is about Cathy Ventura, the woman at the heart of Diddy’s allegations.

Maher has been hesitant to bring back abuse allegations in the past in a confident, ignorant monologue, saying, “If you can’t get justice in pain, can you at least get a receipt, a coupon?”

To deny the real barriers women continue to face the legal system in order to assume greed is why women sometimes seek civil penalties rather than criminals. So nodding astonished by the stereotype that the victim is poor and opportunistic, disingenuously classifies throwing a “coupon” there.

Sadly, he’s far from the only person attacking Ventura. President Trump, who was found responsible for E. Jean Carroll’s sexual assault, tried to curb Combs’ chances of pardon if he was found guilty.

Maher went on to say, “Things have changed enough,” and say they should expect women to report abuse and attacks immediately.

“(d) I won’t tell you any more about your concurrent accounts that I told two friends ten years ago. Tell the police immediately,” he spoke. “Don’t wait ten years. Don’t journal about it. Don’t turn it into a one-woman show. Most importantly, don’t keep F.”

Ami Carpenter, assistant professor of Joan B. Clock Peace Studies at the University of San Diego and an expert on human trafficking, told me she didn’t agree with Maher to put it gently.

“We tend to think of victims as appropriate or undesirable for care and compassion,” she told me. And a lot of it depends on the way they present themselves.

In some instances of Ventura, and perhaps some of the other women who testified against the comb, alleged abuse continued for years. She and others may have had traumatic ties with Diddy, like many survivors of long-term sexual violence, including sex trafficking and intimate partner abuse.

The Panic of Maga Immigrants sold us the image that traffickers sneaked across borders into the image of being members of the Latinx cartel, but the reality is that most of the victims are here in America, and at some point, they trust them. It’s a friend, a mentor, a man who provides protection from otherwise difficult lives. A comb-like person with power, money and promises of a better life.

And only after the relationship has been formed would it be when abuser cycling is between “abusive behavior and expressions of affection and regret” that began to trigger trafficking, often leading victims to a mix of confused and numbing emotions, including “sympathy, compassion, and even affection for the abuser.” Because that’s what the abuser wants.

In a 2016 survey, Carpenter spoke to 65 San Diego area sex traffickers about how they controlled the victims.

“They all knew how to create this psychological connection for people with their victims,” she said. “In fact, they didn’t know the power of words, so they looked down at traffickers and magazines who had to resort to violence with words. For them, it’s all manipulation, mental manipulation.

Dr. Stephanie Richard, Law Professor at Loyola Law School and director of Sunita Jain Jain’s Trafficking Policy Initiative, believes that fights and flights are about resisting abuse, violence, freezes and traumatic responses that are common to fawns, but there are also people trapped in long-term abuse.

“Many victims realize that if they’re fading, they won’t be harmed,” Richard said. “And this kind of reaction is someone who is trying to keep them safe because we are all human and we cannot live in such a scary thing without protecting ourselves.”

It’s like agreeing to the abuser or even accepting the text. It is expected that at least three women, along with Ventura, will be testifying against the comb. The two “Mia” and “Jane” are already trying to remain anonymous, but Mia is already out. Briana Vongolan, a third Ventura friend, testified that Combs once hugged her on the balcony railing and left her ordered before throwing her into the furniture on a nearby patio.

During cross-examination by Combs’ lawyers, Mia burned for hours on friendly texts with Combs and whether the abuse actually happened. Trying to trust Combs’ testimony that he once hit the door on the arm, the defense attorney asked if she cried out. Does it sound familiar?

Ultimately, Mia explained her behavior in seven words that survivors would understand: “When he was happy, I was safe,” she testified.

And that’s really what it’s tied to for all women: a sense of safety.

Whether in court, online, in the media, or in the common society, they explain not only how they survived, but how they survived until they are convinced that women are safe when speaking to abusers and others.

Maybe they found the courage to prevent the same pain from being inflicted on someone else?

[ad_2]Source link