[ad_1]

Five years have passed since May 25, 2020, and George Floyd was breathless under the air under the knees of a Minneapolis police officer at the corner of 38th Avenue and Chicago Avenue. Five years after 17-year-old Darnella Frazier stood on the curb outside the cup, he witnessed a 9 minute 29 seconds galvanized the global movement against racial inequality.

Frazier’s video didn’t just show what happened. It insisted on seeing the world as a halt.

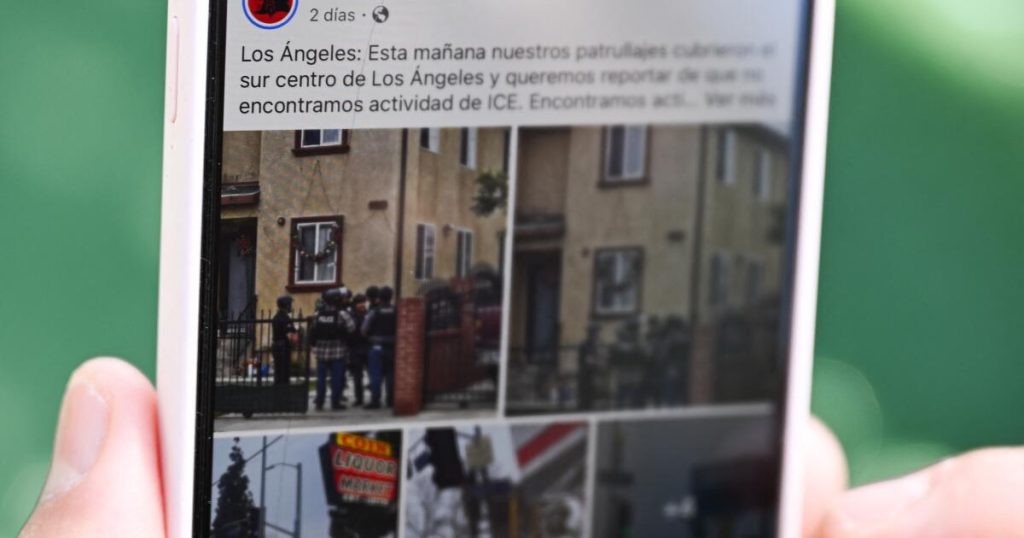

Today, its legacy lives on in the hands of different communities, facing different threats, but wielding the same tools. All over the US, Latino organizers are hiking their phones and registering them on records rather than going viral. They livestream immigration and customs enforcement raids, filming family separations and documenting protests outside of detention centres. Their footage is not satisfied. That’s proof. It’s a warning. That’s resistance.

Here in Los Angeles, I teach journalism, and some images burned myself into public memory. One viral video shows her bondage father stepping into a van without a white mark. His daughter sobs behind the camera, pleasing not to sign official documents. He turns and gestures to make her calm before blowing her a kiss. A LAPD officer on a horse that was charged with peaceful protesters across town.

In Spokane, Washington, residents formed voluntary human chains around their undocumented neighbors. In San Diego, the White Allies cried out “Shame!” as they chased a uniformed National Guard car from their neighbourhood.

The impact of smartphone witnesses is both immediate and unmistakable, and is the innards of street earthquakes. On the ground, the video fueled the “No Kings” movement, which organized protests in all 50 states last weekend. Legislators are responding too – sparks flying in the Capitol hall. As President Trump strengthens immigration enforcement, democratically-led states are delving into the state laws that restrict cooperation with federal agents.

Local TV news reports have included Witnesses smartphone video, which helped them reach a larger audience.

What’s unfolding now is nothing new. It looks new. Latino organizers are drawn from a playbook that became sharp in 2020. One is rooted in a longer lineage of black media survival strategies built between slavery and Jim Crow.

In 2020, I wrote about how Black Americans use a variety of media formats to fight for racial and economic equality, from slave stories to smartphones. I insisted that Frederick Douglas and Ida B. Wells were doing the same job as Darnera Frasier. It uses journalism as a tool for sighting and behaviourism. Latinos filming the nation at an overreach moment in 2025 – Archives injustice in real time – adapt, expand and continue the work of black witnesses.

Furthermore, Latinos use their smartphones to create digital maps as much as blacks mapped freedom in the age of slavery and Jim Crow. For example, People Over Papers Map reflects older strains. It’s a black maroon’s resistance tactic. They rob enslaved Africans who fled to swamps and border areas, and form secret networks to capture and warn others.

These early communities shared intelligence, tracked patrols and mapped secret paths to safety. People around paper lead the same logic. For now alone, the hideout is ice-free zones, mutual aid hubs, and sanctuary spaces. The maps are crowdsourced. The boundary is digital. The danger is still very real.

Similarly, the Stop Ice Raids Alerts Network brings back the blueprint of the Civil-Rights era. In the 1960s, activists used extensive telephone service lines and radio to share protest routes, police activities and safety updates. Black DJs often hide temporary dispatches as traffic or weather reports. “Crowd on the south side” means a police hindrance and indicates violence that features a “storm warning.” Today, its infrastructure lives up to date through WhatsApp chains, encrypted group texts and story posts. The platform has been changed. The mission is not that.

Layered across both systems is the DNA of the Negro Driver Green Book. This is a guide that once helped black travelers navigate Jim Crow America by identifying safe towns, gas stations and accommodations. Those surrounding the papers and stolen ice attacks are digital descendants of their heritage. Survival through shared knowledge, protection through mapped resistance.

It’s not because of spectacle that the Latino community is using smartphones at this moment. It’s for self-defense. In cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and El Paso, “Ice is nearby” begins as a whisper – now competes on Telegram, Whatsapp and Instagram. The knock will be live stream. The attack will be a receipt. The video will be a shield.

For undocumented families, risk is a reality. Filming is revealing yourself. Going to a live show means becoming a target. But most do that anyway. Because silence can be fatal. Because invisibility protects no one. Because if the story is not captured, you can reject it.

Five years after Floyd’s final breath, the burden of proof remains the most vulnerable and the heaviest. America demands footage before anger. Tape before reform. Visual confirmation before compassion. Still, justice is never guaranteed.

However, in 2020, I was able to tell you that smartphones can destroy the status quo with your right hand. In 2025, the lesson resonated again, this time through the lens of a Latinos mobile journalist. Their footage is unbearable. emergency. Righteous. It connects the dots between ice raids and excessive polyclines, between the boundary cage and the city prison, between the knees in the neck and the door kicked at dawn.

These are not isolated events. They are the same narrative chapters of government repression.

And the cameras are still lying around – and people are still recording – those stories are being told new.

Five years ago we were forced to see what was unbearable. Now it is shown that we cannot deny.

Allissa V. Richardson, an associate professor of journalism and communication at USC, is the author of Bearing Withing While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism. This article was created in collaboration with the conversation.

[ad_2]

Source link