[ad_1]

(WGN) – Herpes can cause herpes.

One scientist is estimated to affect 80% of the world’s population because it has been so ubiquitous in virus research over 30 years. And now, he and his team say their findings may apply to another illness that affects millions.

The research is led by Dr. Deepak Shukla, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Illinois University of Chicago. The virus is herpes simplex 1.

“(herpes) is a quiet virus. I like to live quietly in our neurons,” Shukla said.

Herpes is hidden by the trigeminal nerve that extends into the eyes, nose and mouth, where it produces cold pain and fever blisters. It spreads through tears and saliva. Stress and the affected immune system can reactivate the virus.

Credit: WGN

“So there’s a constant battle between viruses that try to replicate in neurons and host systems that try to suppress them,” Shukla said.

To shock herpes spread through the eyes and nose, the team injected the virus directly into the mouse’s nasal cavity.

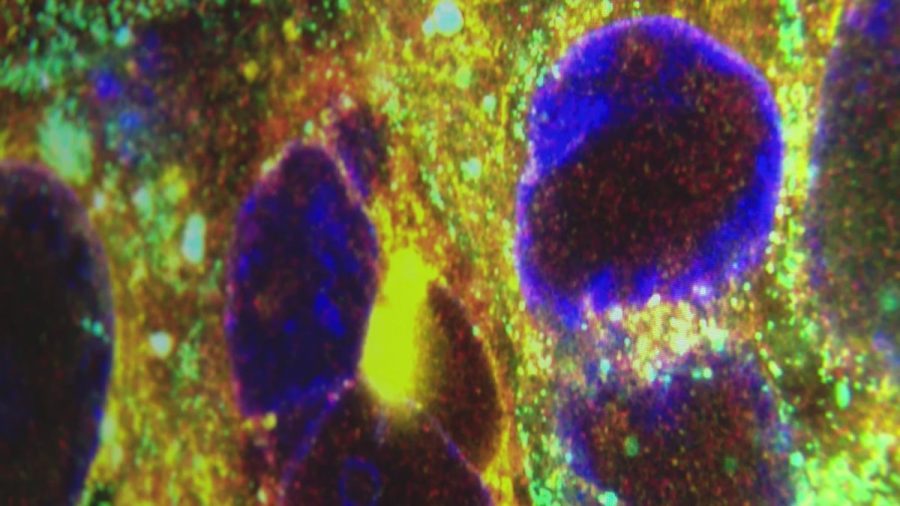

“The virus caused chaos in the brain, killing or inflating bundles of neurons.

The effects of herpes virus on the brain have changed the behavior of animals. Mice were worried and experienced motor disorders and cognitive problems.

“What we’ve shown to (the mouse) is an extreme possibility, but over time, the virus is hidden in our neurons and is reactivating regularly, so the same can happen in humans,” Shukla said.

A specific enzyme called heparinase played an important role in inducing brain damage. This is the same enzyme known to increase in different forms of cancer.

“Not only simple cancers, these are metastatic cancers…the majority of them have high heparinases,” Shukla said.

Heperinase protects cells from death – good in healthy cells. But when a cell gets infected, it also wants to live. There, heperinases and herpes appear to work together to promote scattering. The same can be said for cancer cells. When hepinase was not present, Shukla said there was an interesting discovery.

“Animals that didn’t produce any heparinase,” he said. “They were fine, they had no problems – the same amount of virus is the same rate.”

Shukla says the ultimate goal is to teach heperinase the difference between good and bad cells.

The next step is to develop non-toxic hepinase inhibitors that can be tested in animals and ultimately in humans.

[ad_2]Source link