[ad_1]

He was, in the eyes of the FBI, a rare and dangerous man, a combat enforcer who returned from Vietnam to engage in the founding war.

“We’re going to drive pigs out of the community,” Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt, the 21-year-old leader of Los Angeles’ Black Panther Party, told reporters in 1970.

Pratt was sturdy, compact, level-heavy and plagued his childhood with the Louisiana Bayou. He imagined a violent end at the hands of the police, and he put it out as an occupation force in an African-American neighborhood. “The next time I see me, I might be dead.”

When he went to trial in 1972 – the charges made him murder a white school teacher, execution style, during a robbery – he claimed he was framed.

His defense attorney, young Johnny Cochrane Jr., initially dismissed Pratt’s speech as paranoia. However, Cochrane would later describe the incident as “a Twilight Zone of deception, injustice, betrayal and official corruption.”

Pratt’s belief kept him behind bars for 27 years, plagued by Cochran, who believes that Pratt is innocent and made a mistake in a trial that prosecutors skillfully exploited. It will be years before the authorities’ war against the perceived destroyers reveal how bravely they have been fooled.

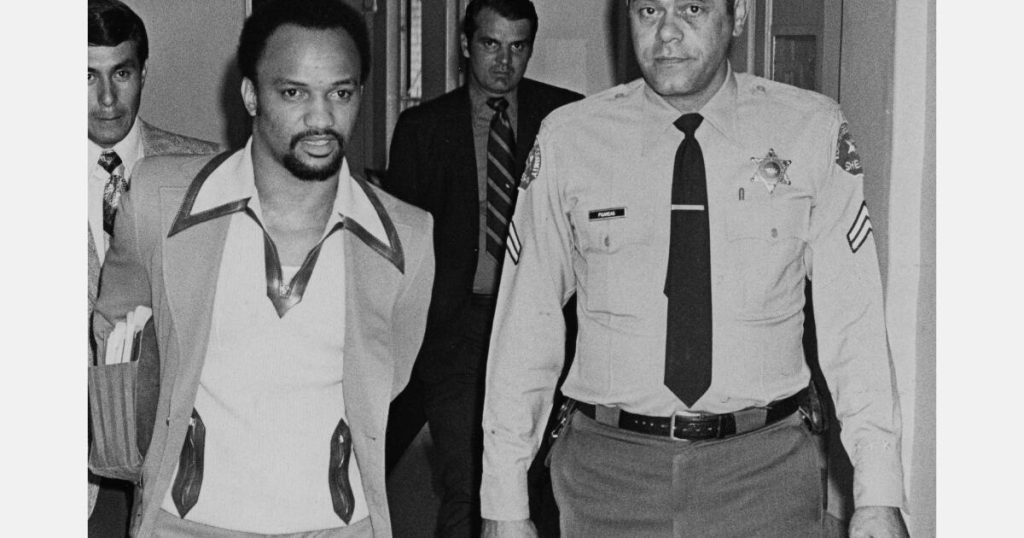

Attorney Johnny Cochran on the left will describe Pratt’s murder charge as “a dusk zone of deception, injustice, betrayal and official corruption.”

(Photo of Jim Louismen/Pool)

“It looked at the surface like a really simple murder,” says Stuart Hanlon, now 76, at 76, the radical San Francisco defense attorney who took Pratt’s suit as a law student and pursued it for decades.

The victim was Caroline Olsen, 27, who was with her husband on the Santa Monica tennis court in December 1968 when a pair of gunmen approached demanding money. The man ordered the couple to lower their faces and then began firing. She was fatally wounded. Her husband was hit but survived. The robber won $18.

The investigation was stuck and Platt was not a suspect until 1970 when a former police officer was involved with him at Byteers, the Julius “Julio” Butler. Butler himself was a Panther and had resented the promotion of Pratt as the leader of Los Angeles.

In this series, Christopher Goferard revisits old crimes since Los Angeles, from famous people to forgotten people, to the consequences of unforgettable people, and the memories of those who were there.

Butler, a witness to the state star, testified that Pratt stopped by his beauty shop, announced he was going on a “mission,” and later pointed out an article about the shooting to confirm what Santa Monica was doing.

Cochrane asked Butler if he was a police informant. Butler completely denied this.

Devastatingly for his defense, Olsen’s widow pointed to the defendant and said, “That’s the man who killed my wife.”

Cochrane opposed the reliability of interracial witness identification, especially under conditions of stress, and placed witnesses on stands who saw Pratt in the Bay Area around the time of the murder. He also wore a platte, which was decorated for heroism along with the Army on two tours in Vietnam, showing what Cochrane called the “soldier light empty” for those who shot the helpless Olsen in the back.

At a 1996 press conference in Los Angeles, Cochrane and other lawyers are calling for a new trial for Pratt.

(Nick UT/AP)

Cochrane thought it was a case of winning, but he presented an exhibition that backfired badly. It was a Polaroid given to him by the brothers of Pratt. It showed Pratt’s beard, but it contradicts Shooter’s widow’s first description and “clean shaved black man.”

Prosecutors rebutted with Polaroid employees who said the film wasn’t being made until five months after the crime.

The ju judge took him 10 days to find him guilty of first-degree murder. The sentence was 25 years of life. “You’re wrong. I didn’t kill that woman,” exploding Pratt. “You’re a racist dog.”

Pratt spent the next eight years in solitary confinement. He was closed between prisons and was eventually allowed to visit the couple. His wife gave birth to two children. During a series of failed parole hearings, the panel waited for him to say he was sorry. He claimed he hadn’t done that.

“The last person I killed,” he would say, “I was in Vietnam.”

He was released outside Los Angeles Court in April 1996 and is a supporter of the Pratt Lary for his release.

(Susan Sterner/Applications)

There were many things the authorities hadn’t shared with Pratt’s defense team. They did not reveal that Olsen’s widow had previously identified another man as the shooter. (The man was in prison at the time, but he couldn’t do that.)

He also did not disclose the scope of Starr’s Witness work as a law enforcement officer informant. Based on FBI documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, Pratt’s attorneys have pieced together dozens of photos of Butler’s intimate involvement with the FBI, the Los Angeles Police Department and the LA County District Attorney’s Office.

For FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the Panthers were the most dangerous group in the country, homemade terrorists with weapons stockpiling and amazing Maoist rhetoric. His secret Cointel Pro program was a campaign of spy, eavesdropping and sabotage aimed at destroying perceived destroyers and hampering a “coalition of extremist black nationalist groups.”

“Geronimo was a natural leader and he was targeted by the FBI,” Hanlon said.

When Hanlon stitches the documents together, it becomes clear that Butler was helping. However, in denying the appeal after the appeal, the court ruled that Butler was not an informant – he “was a contact and nothing more,” and Pratt was unworthy of the new trial.

He was still considered dangerous. “If he chooses to set up a revolutionary organisation when he is released from prison, it’s certainly easy for him to do so,” the prosecutor said at a single parole hearing. “He has this network.”

When the defense attorney brought evidence to the county at the time. Atty. Gil Garcetti presented it in 1993 as an opportunity to revoke the fraud that his predecessor had approved 20 years ago. However, Garcetti’s reviews were handed over for years, and the lawyers once again relied on the court.

“He’s more likely than anyone who actually committed the crime,” the former LA County district. Atty. Gil Garcetti recently said of Pratt.

(Ken Lubas/Los Angeles Times)

This time, the court granted the hearing. Because the LA County Superior Court bench was denied – the former prosecutor is now a LA County judge and potential witness – the case has been moved to Orange County Superior Court. For Platt’s supporters, this caused the cold. What hopes did they have for a stubbornly conservative county?

However, Judge Everett Dicky surprised them.

“It’s clear that this isn’t a typical case,” Dickie said. “It screams for a solution.”

This time, Pratt’s team was armed with evidence that he had never heard of in the original trial. They had the testimony of a retired FBI agent who supported Pratt’s claim that he was in Oakland during the murder.

They knew that the DA’s office allowed Butler to not contest the four felony in exchange for probation.

And they had an index card recently discovered by one of Garcetti’s investigators in an Office file that listed Butler as a DA informant. Submitted under B. It was there all along.

“It never was handed over to the defense. Why didn’t they turn this over?” Garcetti said in a recent interview. “I couldn’t find anyone troubled by the fact that ‘Yeah, I had that document in a file’. ”

Still, Garcetti’s prosecutors downplayed the importance of the cards. Butler was not an informant, they argued vigorously, but simply “sauce”.

In late 1996, Cochrane finally got the opportunity to stand up to Butler. He had been waiting for years. Butler became a prominent Los Angeles Church lawyer and staff. He claimed he was simply a “connection” between law enforcement and the Panthers.

Cochrane asked him what the definition of an informant was. He admitted that he told the FBI that Pratt had a submachine gun. He said his definition of informant was the person who provided the accurate information.

“So, under your own definition, did you let the FBI know?” asked Cochrane.

“You can say that,” Butler said.

Pratt shines after his release from the Orange County Jail in June 1997.

(Kim Crush/Getty Images)

Dickie abandons Pratt’s beliefs and concludes that Butler is lying and that the prosecutor has hidden evidence that could lead to Pratt’s innocence.

Pratt was released on bail in June 1997 to cheers from his supporters.

“The biggest moment in my legal career,” Cochrane called it.

“I went home to Morgan City, Louisiana to see my mom and my home fork,” he said. “It wasn’t easy to come here.”

He said he wanted to hear the rain on the tin roof of his childhood home.

However, Pratt’s legal challenges were not over. Garcetti pleaded that he had not found any evidence to point to Pratt’s innocence. He did not lower the case until February 1999 when the Court of Appeals lined up on Pratt. The following year, Pratt won $4.5 million in false control lawsuits against the City of LA and the FBI. He bought a farmer in Inbaseni, Tanzania, and enjoyed dating former Black Panther Pete O’Neill, who fled the United States in 1970.

O’Neill discovered he was dead at his home in May 2011. Pratt was hospitalized with high blood pressure. This had been bothering him for years, but tore his IV home. He hated confinement. He was 63 years old.

“We always say, ‘The system works,’ but no, because the system, the community and the band of lawyers fought against the system, the system produced the right results. The system doesn’t work on its own.” “They took half of his life and they couldn’t break him.”

So who killed Caroline Olsen? Hanlon believes the murderer is another Black Panther. This is a pair of heroin addicts known to inflict habits in armed robbers. They died violently in the 1970s. One was shot and the other was thrust into a fence while robbing.

In a recent interview, Garcetti, one of the longtime defense team’s main antagonists, said his views on the incident have evolved. Looking back, he regrets fighting to keep it alive.

“It’s more likely he’s face valued than the person who actually committed the crime,” Garcetti said.

He said he learned more about the US government’s tactics against disadvantaged groups in the 1960s and ’70s.

“I’ve read enough from Top Down to know that the FBI was working to isolate unknown leaders of the Black Panther Movement. It doesn’t shock me to know that they have pursued people who have not actually committed the crimes that succumbed to removing them from the scene.”

[ad_2]Source link