[ad_1]

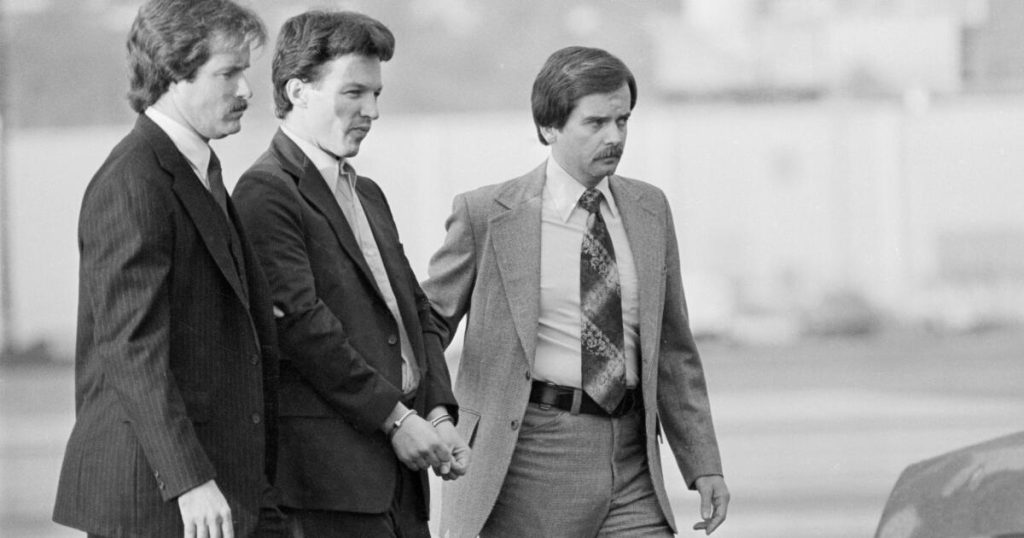

Christopher Boyce and Andrew Dorton Lee were childhood friends, the altar boys raised in Catholic Pews, and were a prosperous outskirts of the Paros Vedes Peninsula.

By the mid-1970s, Boyce was mad about the Vietnam War and Watergate. He was a liberal, stoner and Falcon’s lover. Lee, the doctor’s adopted son, was a cocaine and heroin pusher swirling with addiction.

The way they became spies in the Soviet Union was a iconic story of Southern California in the 1970s, where the state’s massive Cold War aerospace industry collided with youthful anti-establishment currents.

Everyone agrees that it should have been impossible.

In the summer of 1974, Boyce, a bright and dissatisfied 21-year-old college dropout, got a job as a store clerk at the TRW Defense and Space Systems Complex in Redondo Beach. He won appetizers through the Old Boys Network. His father, who carried out security for aircraft contractors and was once an FBI agent, was a positive call.

In this series, Christopher Goferard revisits old crimes since Los Angeles, from famous people to forgotten people, to the consequences of unforgettable people, and the memories of those who were there.

Boyce earned $140 a week at the defense factory and continued to groom his second job. TRW investigators were only performing some weird background checks. They skipped his mate. He may have revealed his link to his drug culture and Lee, who had already had multiple drug busts and serious cocaine habits.

“The Falcon and the Snowman,” in account of the incident in Robert Lindsay, the author explains the voice to start the day by popping and engaging amphetamine after a shift in the parking lot of TRW. Falconry was his greatest passion. “Before Christ implants Chris into their time, he will fly the falcon in the exact same way men have done for centuries,” Lindsey wrote.

Boyce was impressed by his boss and was soon allowed to enter a fortress of steel equipment known as the “Black Vault.” This is a classified sanctuary exposed to sensitive CIA communications related to a network of American spy satellites. The satellites eavesdropped on Russian missiles and defense facilities. Some of the targets were to stop a surprising nuclear attack.

Reading the CIA Communique, Boyce didn’t like what he saw. Among other crimes, he decided to deceive Australian allies by hiding satellite information the US government has shared and promised to interfere in national elections.

“I was completely indistinguishable from the overall direction of Western society,” Boyce said in the era years later. He attributed his spying opportunities to “synchronize” and explained, “How many children can get a summer job working in a safe with encrypted communications?”

Soon he made the “bigest, stupid decision” of his life. He told his partner Lee that they might sell the government secrets to the Soviets. Lee spoke to the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City. There, the Russians gave him caviar and bought confidential documents with toast “to peace.”

Lee’s KGB handler has devised the protocol. When he wanted to meet, he tapes an X to the ampposts at designated intersections around Mexico City.

For more than a year, thousands of classified documents flowed from the TRW complex to the Soviet Union, and Boyce occasionally smuggled them with potted plants. In exchange, he and Lee received an estimated $70,000.

At the party, Lee showed off his miniature Minox cameras and boasted that he was engaged in spycraft. In January 1977, desperate for money to fund the heroin contract, he fled to the directions of the KGB and looked unannounced outside the Soviet embassy. Mexican police thought he looked suspicious and had arrested him.

He held an envelope containing FilmStrips, which recorded a US satellite project called Pyramider. Under the question, Lee reveals the names of his conspirators and childhood friend. Boyce had just returned from a densely packed trip across the mountains.

The two men’s spying has presented a special challenge to the US Lawyer’s office in Los Angeles. The Carter administration was ready to pull out the plug of the case if it meant airing too many secrets, but a strategy was devised. Prosecutors focused on pyramidal documents, including systems that had never actually descended from the ground.

Joel Levine, one of the US lawyer assistants who indicted Boyce and Lee, said only a small portion of what he sold to the Soviets came to court.

“We were told that these other projects should not be revealed. It is too expensive for our government to prosecute in whole or in part,” Levine said in a recent interview. “You have to leave from that.”

For federal prosecutors in LA, hanging in the case was a memory of recent humiliation. The collapse of the Pentagon thesis trial as a result of the Nixon administration’s attempt to bribe judges with work. It surprised the prosecutor.

“If that happens, I was worried that it would ruin our reputation forever,” Levine said. “So we made it very clear that if we smelled that, we would step into court and dismiss the case ourselves.”

The defendant had a completely different motive. Lee was in it for the money, one of the prosecutors, Richard Stills, said in a recent interview. But “Voice was completely ideological. He wanted to do damage to the US government,” Stillz said. “He just hated this country.”

The defendants were subject to separate trials. The rifts that were growing between them deepened with mutually hostile defenses. Lee’s defense: Boyce led him to believe he was working for the CIA and misinformed the Russians. Nevertheless, the ju judge convicted Lee of spying, and the judge gave him the term of life.

Boyce’s Defense: Lee threatens to reveal a letter he wrote, throwing it at Hashish, threatening him to spy while claiming secret knowledge of the CIA misconduct. Ju-dean also found Boyce guilty, and the judge gave him 40 years.

In January 1980, at the federal prison in Lompoc, Boyce hid in a drain and sprinted freely across the fence. He had been running for 19 months. He stolen banks in the Pacific Northwest until federal agents caught him outside the Washington state burger joint.

He was convicted of bank robbery and won another 28 years. In 1985, the same year the popular film adaptation of “The Falcon and the Snowman” was released, with Boyce testifying to the despair of attending the life of a spy on Capitol Hill.

“There was no thrill,” he said. “There was only depression, and there was a hopeless enslavement of an inhumane and compassionate foreign bureaucracy.

He spoke about being allowed to easily access materials classified under TRW. “Security was a joke,” he said. “We used a code breaking blender to make banana daiquiris and my thice.”

Kate Mills worked as a paralegal in San Diego when he was fascinated by the incident after reading Lindsay’s books. She thought Lee was unfairly malicious and spent the next 20 years fighting to win his parole.

She received letters from prosecutors and sentencing judges in support of Lee’s proving progress towards rehabilitation. He took classes in prison and became a dental technician. He earned parole in 1998.

She turned her attention to releasing Voice, whom she had fallen in love with. She wrote to the Russians, asked how much the stolen TRW document was worth, and received a fax claiming it was useless. He left in 2002 and they got married. They later divorced, but remained nearby. Both live in central Oregon.

Stilz claims that the damage to America was “huge.”

“In a murder, there’s one victim and someone dies,” Stillz said. “In the case of spying, the whole country is the victim. We were more advanced than the Russians in spy satellite technology. They leveled the arena, and that’s probably the most important point.”

He does not give credibility to the Russian government’s claim that it is worthless from the secret information. “Of course they’ll say that,” Stillz said. “What do you think they’ll say? ‘Yes, that allowed us to catch up with the US in terms of spying.’ They’re not going to say that. ”

Kate Mills Boyce said that his childhood friends, best friends Boyce and Lee, were no longer talking, and the silence between them hurt Boyce.

“He said, ‘I love that guy. I’ve always loved him. He was my best friend.’ It hurt him so badly. ”

She said Boyce, now in the 70s, lived a lonely life and was immersed in the world of falconry. “His life, and I have not given birth to you, but falconry,” she said. “He will die with a falcon in his arm.”

She thinks part of what pushed him into the world of spying was a challenge. “I think his unusual and clever people have led him on a whimsical path that has become a miserable path not only for him but for everyone involved,” she said.

[ad_2]Source link