[ad_1]

By the time 44-year-old Marvin Gay moved to a big rambling house with his parents in a South Gramercy location, his cocaine habits were serious and his delusions were deeper. The enemy was conspiring against him, he feared. He gave his father a .38 caliber revolver. To protect the house, he said. He was completely circulated from childhood, to live with his mother who worshiped him and his disapproved father who killed him.

It was 1984. It may have been a triumphant era for the vocalist known as the sensual soul king. The previous year, he finally won two Grammy Awards after decades of nominations. In Inglewood’s NBA All-Star Game, he offered a slowdown version of the Starspangle banner, which redefined the national anthem. He was broken from his longtime label Motown with his hit comeback album “Midnight Love” and one of his signature song “Sexual Healing.”

Suave Tenor, a long-standing sex symbol with a restless risk taker and elegant playboy persona, Gay had another world voice. His falsetto found a new register of joy and longing. His songs were married to physical and spirituality, along with the echo of a little boy singing in the Gospel Choir of his father’s church.

In this series, Christopher Goferard revisits old crimes since Los Angeles, from famous people to forgotten people, to the consequences of unforgettable people, and the memories of those who were there.

“My dad was a pastor,” Gay said. “And when I started singing, it was for him.”

Growing up in the slums of Washington, DC, he inherited his father’s strict Pentecostal Christianity and the concept of discipline, heaven and hell. His relationship with Marvin Gay Sr. had little connection with Marvin Gay Sr., a jealous man who drank hard and dressed, a habit that embarrassing young singers.

They were at war from the beginning. The father beat his son regularly and corned non-religious music as a demonic work.

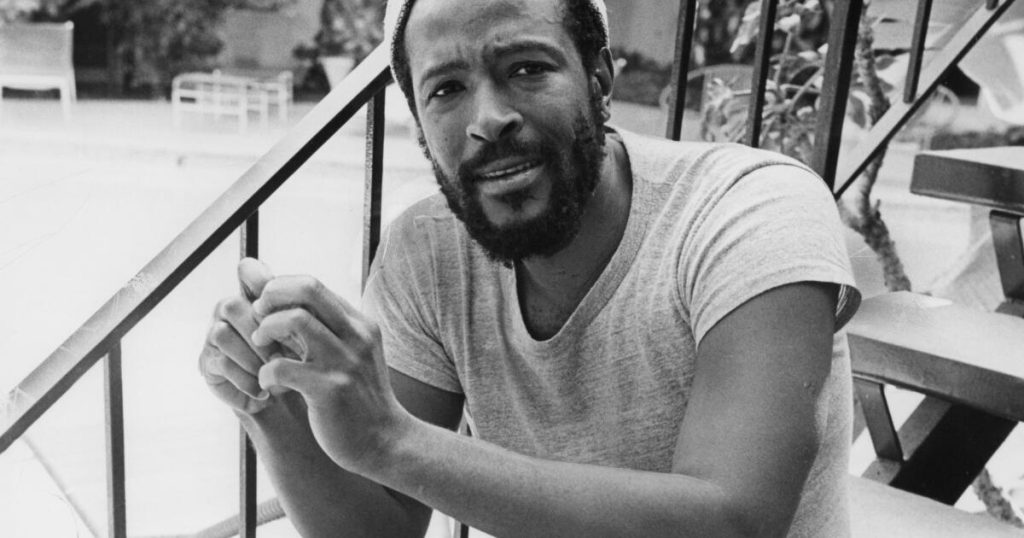

Los Angeles’ Marvin Gay, soul singer, songwriter and musician.

(George Rose/Los Angeles Times)

“My husband didn’t want Marvin,” Alberta, the singer’s mother, told the biographer. “And he didn’t like him. He said he didn’t really think he was his child. I said he was nonsense. He knew Marvin was him. But he didn’t love Marvin. What’s worse, he didn’t want me to love Marvin either.

In “The Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gay” by David Ritz, Gay described his father as “a very unique, transformed, cruel, and powerful king of all,” saying, “With acquisition of his love was the ultimate goal of my childhood, I hated his attitude.

Gay noticed his jealousy. “I realized that my voice was a gift from God and that I had to use to praise him,” Gay said, but his father “didn’t like it when my song won more praise than his sermon.”

Even if he was bigger than his father, Gay remembered, and the violence continued. “I wanted to fight back, but even raising your hand to your father is an invitation for him to kill you, where I came from.”

It was a volatile relationship, Ritz told The Times in a recent interview, in a complicated interview.

“The man who beat him also led him to God,” Ritz said.

To escape him, the singer dropped out of high school, joined the Air Force, forged a mental breakdown and earned an honorable discharge. He dreamed of being a black Frank Sinatra. He found his surrogate father at Motown founder Berry Gordy and became the famous Motown Sound architect.

His 1968 version of “I Haped It Standard the Grapevine,” a song about a man who was tormented by rumors of his lover’s affair, was a hit. Gay drew inspiration from his broken marriage with Goldy’s sister.

His father hated his job. His mother rose at the age of five and cleaned up the house of a rich man. When gay began making money to feed her, it became another source of responsiveness between father and son.

Contrary to resistance from Motown, he gambled on his self-written self-produced “What’s Going.” (Rolling Stone calls it the greatest album ever.)

His social commentary included war, protest, ghetto life, police brutality, pollution, and the nuclear Holocaust. Inspired by his brother Franky, he sang about struggling soldiers from Vietnam. And he sang, “Father’s Father/We don’t need to escalate/You see, war is not the answer.”

As his fame grew, he went into hiding. The worshippers filled his concert seats – the women especially worshiped him – but they felt that love was fleeting and unreliable. “I want to be liked, and I’d hate it. If the audience doesn’t like me, I really hate it,” he told The Times. “It’s a real hang up.”

He disliked the government and corned taxes, but the government realized. By the late 1970s, he had gone bankrupt and had owed $2 million to the IRS. He fled for Europe, chased by his creditors, and it seemed Motown had given up on him amidst a recession in sales. (“I love being respected,” he said. “I was not worshiped here.”)

He spent three and a half years in a self-exile and said, “I’m selfish. I lie, I’m very humble, but I was able to lie that it was a jibe.”

When he toured with the “Midnight Lab” album Gay made for Columbia Records in 1983, Times music critic Robert Hillburn described one of his concerts as a “victorious exhibition” of artistry that marked a liberating break from Motown. “At last, he was standing alone. The artist proved,” Hilburn wrote. “This tour should be the culmination of that artistic climb.”

However, Gay was working on serious depression and the habit of giving away that inflamed his delusions.

He found himself wandering the highway, as if a bold car were hitting him. He had spoken about suicide multiple times – he admitted that he was trying to do it with a cocaine overdose, but couldn’t go all the way. His father’s religion told him it was a fatal sin.

Police and the Los Angeles County Coroner removed Marvin Gay’s body from Los Angeles Hospital after being declared dead on April 1, 1984.

(Nick UT/AP)

In early 1984, gay, who had divorced twice, returned with her parents. I lived in the hall from my father on the second floor of my family’s brick Tudor in Los Angeles’ Crenshaw neighborhood.

As Frankie Gay, who lived next door, wrote his memoir, “Marvin Gay, my brother,” it was a “madhouse,” where screaming matches often occur.

The musicians opened holes in their bedrooms, guns in their pockets, Bibles in their hands, and steadily visited by drug dealers. His 69-year-old mother dots on him, cooks for him, rubs his legs, prays with him.

The often drunk father replied to her loss of attention. He placed a .38 revolver, a gift from his son, under his pillow.

The fatal conflict was on April 1, 1984. The father came to his son’s bedroom and criticized his wife for misguided letters from the insurance company. The singer kicked him out of the room and took him into the hall, “squeezing his father quite well,” police said.

My father returned with a gun and shot his son twice, once in the shoulder, once in his heart. When the news came out, I initially thought it must be an April Fool’s Day twisted joke. Some, like his biographer Ritz, considered it to be the pinnacle of a gay death wish.

An estimated 10,000 fans and mourners have been found to pay homage to Marvin Gay Jr. at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Los Angeles.

(Ian Dryden/Los Angeles Times)

At Forest Lawn Memorial Park, 10,000 fans stood on the one mile line to say goodbye. It was estimated to be the largest crowd in the park’s history.

On the probation officer’s account, Gay said his son pushed him against the floor and kicked him, and he grabbed the gun from under the pillow, fearing further attack. A Los Angeles prosecutor charged him with murder, but found himself in a weak case.

Toxicology reports showed cocaine in the singer’s system. A court-ordered brain scan revealed that the 71-year-old defendant was suffering from a walnut-sized brain tumor.

Additionally, the defendant’s photograph shows his body covered with fresh bruises, suggesting that he had a hard beating from his son. Donna Blacke, who charged the case, recalled that one of the bruises on his side was melon size. “I thought, ‘It’s not a punch, it has to be a kick,'” she said in a recent interview. “Obviously, it was a big fight.”

This supported the case of self-defense. Arnold Gold, one of Marvin Gay Sr.’s defense attorneys, told The Times in a recent interview, Arnold Gold, one of Marvin Gay Sr.’s defense attorneys, told The Times:

“I had sensational defence facts, but at least the only witness was my mother,” Gold said, “she refused to testify.”

The murder detective led Marvin Gay Sr. to LAPD headquarters on April 1, 1984, handcuffed the day he shot his son.

(Lennox McLendon/AP)

Gold said that he is refraining from reducing unwilling manslaughter charges, but “everyone wanted to resolve the case as quickly as possible.” And Marvin Gay Sr. accepted the deal five months after the shooting, when prosecutors allowed them to sue a contest on voluntary manslaughter charges.

The conviction may have put him in 13 years’ prison, but the probation department was recommended for lockups, so little hopeful the judge would struggle with him. Gold remembers about his clients: “How sad and pathetic he was.”

The legal process unfolded in a relatively quick and calm manner without any significant controversy or protest. “This was one of the first famous criminal cases, but there was no polarization that OJ Simpson had, for example,” Gold said. Both parties were black, so “we had no racial elements that we thought could be exploited.”

Prosecutor Bracke said he was surprised that there was little turmoil surrounding the case. “I thought someone would call me,” he murdered his son. You let him go. “I had nothing. ”

She said she had a conversation with a black record clerk. “I said, ‘Where are the shades and the crying from the community?” This was clearly a favourite son and she was very quiet. ”

Some gay families, such as his brother Frankie and his sister Jeanne, concluded that gay had adjusted his own death. She said her father revealed that if Marvin hit him he would kill him.

By provoking his father, he ends his misery and frees his mother.

Ritz said he sees it as a crime rather than a tragedy and as an elaborately choreographed suicide that has the effect of punishing his father. “He thought his father would go to hell because his father killed him,” Ritz said.

In his memoirs, Frankie Gay explains that he runs into his brother’s bedroom and cradles him when he dies. “I got what I wanted,” the singer muttered, with his brother’s explanation. “I couldn’t do it myself, so I let him do it.”

Prosecutor Bracke notified her account and said she had never heard of it. “He certainly didn’t tell the detectives that version,” she said. “That’s the first thing I’ve ever heard.”

Seven months after he killed his son, Marvin Gay Sr. received probation from a superior court judge who concluded that the singer would cause a fatal conflict and that the prison would be a death sentence for the frail and aging defendant.

Gay Senior, who lived for another 14 years, stood among his lawyers and thanked the judge for his mercy. His voice shaking and he spoke very gently. He said sorry. He said he was afraid.

“I wish he could step on the door right now,” he said. “I loved him. I love him now.”

[ad_2]Source link