[ad_1]

California lawmakers are reviving plans for a major expansion of the Santa Monica Mountain National Recreation Area, but efforts will be placed as the Trump administration seeks cuts in funding that could lead to areas that are disconnected from the national park system.

The law recently reintroduced by Senator Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) adds more than 118,000 acres known as the rims of the Valley Corridors to a recreational area of about 154,000 acres known as the rims of the Valley Corridors, known as the world’s largest urban national park. Rep. Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) will be introducing the house version.

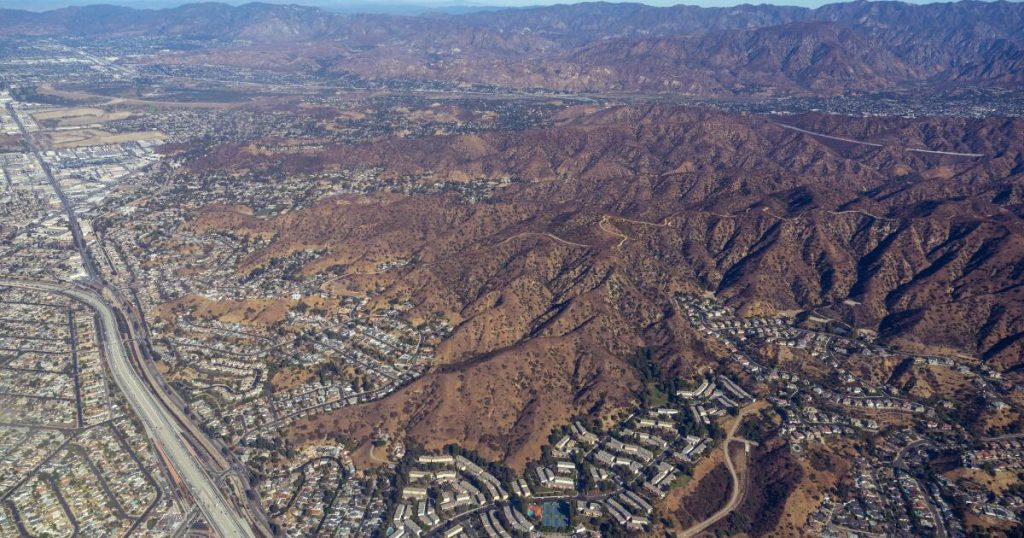

The valley corridor edge is a non-resident area that stretches from the Simmi Hill and the Santa Susana Mountains to the Verdugo and San Gabriel Mountains, creating a “green belt” surrounding San Fernando, Cresenda, Santa Clarita, Simmi and Conejovare. It also includes existing parks and historic sites, such as Griffith Park and Orbera Street in Los Angeles.

A map depicting the edge of the proposed valley corridor. The area added to the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is marked yellow and includes the mountains surrounding the San Fernando Valley.

(National Park Bureau)

Advocates say if the law is successful, it paves the way for cohesive management of vast regions and access to federal funding and expertise. Supporters say it could lead to conservation of wildlife corridors for mountain lions, bears and other local creatures, as well as better maintenance of the trail.

“The intention is to make this publicly available access to national forests and state parks,” Friedman told The Times. “So we’re adding more land, but doing this adds a lot of connectivity and makes it easier for people to enjoy those public spaces.”

A spokesman for the National Park Service declined to comment.

It’s not a new effort. In fact, elected officials and environmental activists have been trying to protect the edge of the valley corridor for decades. A similar law failed last year.

The latest iteration aims to include $900 million for park operations as the Trump administration seeks to cut funds from the National Park Service, or about 30% of its operating budget, next year in fiscal 2026.

When proposing cuts, the administration called for certain federal parks to be transferred to the state.

Park Services’ responsibilities include “a large number of sites that are not “national parks,” in the traditionally understood sense, many of which accept most local visitors and are better categorized and managed as state-level parks,” the discretionary budget request states. “While the budget continues to support many national treasures, there is an urgent need to streamline staff and relocate certain properties to state-level management to ensure long-term health and maintenance of the national park system.”

National Park Conservation Assn is the national park conservation organization. According to an analysis of the country, organizations dedicated to national park conservation, the expected reductions would lead to at least 350 internal organs out of the 433 areas managed by the Park Service nationwide.

Dennis Alguell, director of Southern California at the NPCA, said he expects that if the cut passes, most of the money will go to “marquee parks” like Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Yosemite.

“Participants like the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area are at risk,” he said.

“Only Congress has the power to ultimately dispose of federal property and sell it or return it to the state. “So this administration may have that intent, but in the end Congress will have a last voice — or should have a last voice.”

The budget is just one of several threats to national parks that have emerged in recent months.

In February, around 1,000 National Park Service employees were fired as part of the Trump administration’s push to reduce federal workers, including about eight workers in the Santa Monica Mountain National Recreation Area. The court order overturned the layoffs, but many believe more jobs will be cut.

Since January, the NPCA estimates that Park Services has lost about 13% of its staff due to pressure buyouts, early retirements and postponed resignations.

Ventura County-based civic activist Jim Hines is dedicated to protecting public land, water and wildlife, and has issued a warning about vulnerability in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. In an unofficial May email newsletter, Hines said it had appeared in nearly 10,000 people, and the recreation area is “Doge Target Number One,” referring to the government’s ministry of efficiency, led by Elon Musk.

There’s so much to lose, he wrote in his newsletter.

In an interview, Hines said he would travel to Washington, D.C. regularly to meet with his “enemies,” including Trump administration officials who carry out Doge orders. He has been there five times since Trump began his second term.

Outside the small number of representatives with ties to Southern California, members of Congress have never heard of the Santa Monica National Recreation Area, he said.

“Time to let you know wherever you go about the importance of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area… I started with the Trump/Doge administration… Now the ball is finished with you,” he wrote in his May 12 newsletter.

Hines believes that the vision of the valley corridor edge he supports will one day come true, but this year it is not. He said the latest bill could be “negative zero.”

The concept of the valley corridor edge came from the late Margefeinberg’s master’s thesis in the mid-1970s. Graduate students in Northridge, California imagined long distance trails surrounding the hills and mountains of the San Fernando Valley.

Over the years, politicians and conservationists have taken up Feinberg’s cause.

In 1990, Republican Gov. George Ducmean illuminated the greenery of the completion of the Valley Trail corridor masterplan, but that did not lead to widespread action.

During the George W. Bush administration, Congress funded research on the valley’s edge, and the Parks Bureau was completed in 2016. The bill then passed through Congress and home during the Trump administration, but died in the Senate.

In previous iterations of the law, 191,000 acres of land were added to the Santa Monica Mountain National Recreation Area. These bills have never been taken as they face backlash from developers and construction lobbyists.

Land zoned in residential or commercial zones, or already developed for those purposes, has been removed from the proposal. What remains is the land already protected at the local level.

Schiff’s involvement in the efforts dates back at least 17 years ago.

“The valley rim includes some of Los Angeles’ last wild and open spaces, linking the urban centre and suburbs to beautiful outdoors,” Schiff said in a statement. “The law preserves the land and wildlife that millions of Angeleno enjoy.”

NPCA’s Arguelles said that by looking at the Santa Monica Mountain National Recreation Area, where the National Park Service owns and manages only about 15% of the land, the practical effects of the law can be collected. The federal status of a recreation area is not about controlling the local jurisdiction, he said. Instead, Park Services can work with other land managers, including state and local agents, to restore native vegetation, learn trail networks, and complete other complex projects.

For example, more than 20 years of research into mountain lions in and around the Santa Monica Mountains is directed by the National Park Service. The research sheds light on the existential threats faced by large cats that emit their existence in an increasingly urbanized landscape.

“That’s what we can do in these other areas by applying resources and expertise,” says Arguelles.

Even if the bill “stags” in DC, he said introducing it would help keep the issue alive at a local level.

Times staff writer Jaclyn Cosgrove contributed to this report.

[ad_2]Source link