[ad_1]

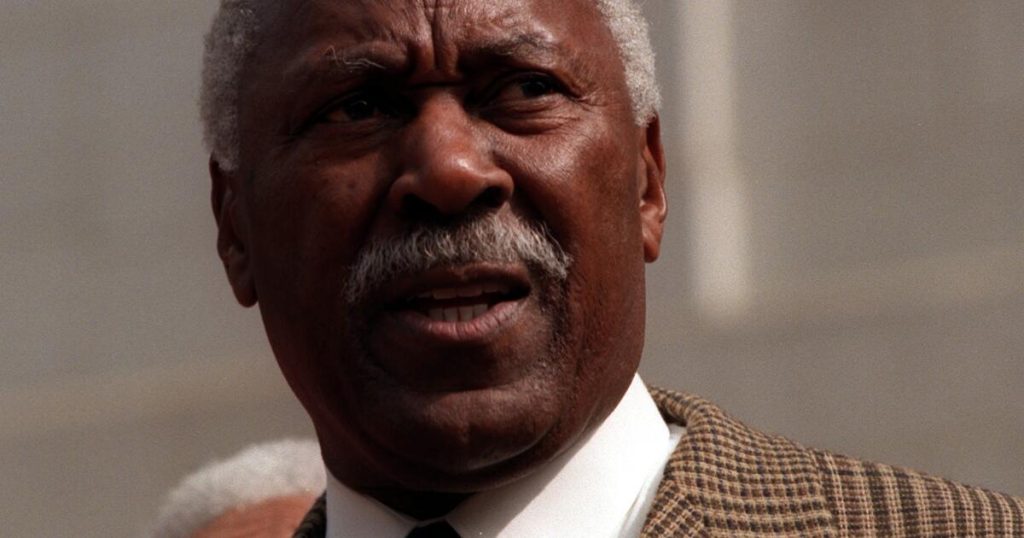

Former Los Angeles City Councilman Nathaniel “Nate” Holden spoke constantly with a sense of confidence and a firm belief in his own destiny.

Born in Macon, Georgia in 1929, it was a kind of belief that was needed to raise the highest class political power in Los Angeles. He represented the area as a state senator and later served on City Council for 16 years.

Holden, a towering figure in LA’s political field, passed away Wednesday at the age of 95.

“Nate Holden was a legend here in Los Angeles,” Hearn said in a statement. “He was a lion in the state Senate and a troop considered on the Los Angeles City Council. I learned to sit next to him as a new councillor.”

Before beginning his political career, Holden served as an aide to Hearn’s father, former LA County superintendent Kenneth Hearn. Young Hearn said she called him Uncle Nate and considered him part of the family.

Holden, a six-year-old Georgia, said he heard the state governor on the radio that he vowed to continue his mission to suppress black people, who were denied the most basic human rights at the time and were frequently targeted by angry white mobs.

He recalled his childhood rebellion against racism that was later fully displayed deep south. He threw rocks into local public pools at a time when only white people were allowed to use them, and once told a white couple while cleaning their backyard that he was planning to become president of the United States.

His father was a breakman in the central Georgia Railroad Company, and when his parents left when they were 10 years old, Nate moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey, where his grandmother lived, along with his mother and siblings.

He is a 16-year-old beginner boxer who knocked out experienced contestants and local champions at his New Jersey gym. In 1946 he lied about his age and joined the US military. He was deployed to post-World War II Germany where he served as a military police officer.

When Holden returned to the United States, he decided to become a draftman. However, he said that one of his teachers intentionally gave him bad grades to stop him, and that such work was out of reach for black men.

When he applied for a training program for military veterans, he was denied again and told him he was wasting his time.

“I have served God and the Kingdom and I will be part of that training program,” Holden said. “If I don’t get it, I’ll go to Washington and knock on that president’s door.”

He finally got hospitalized and studied design and engineering in the evening while graduating from high school. He eventually worked for several aerospace companies, which led him to California.

Holden made his first foray into politics as a member of the California Democratic Council, a left-leaning reform group. He lost his parliamentary bid after campaigning as an opposition to the Vietnam War, but also became president of a democratic reform group.

After being elected to the California Senate in 1974, he helped create the state’s Housing Finance Discrimination Act. This has prohibited financial institutions from discriminating based on race, religion, gender, and marriage status. He also supported a law that required California public schools to commemorate the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr.

Holden left the Senate after a term, ran for Congress again, losing once more. In 1971 he became the assistant assistant to LA County Superintendent Kenneth Hahn, a popular white politician in a very black district.

By the time Holden turned his eyesight towards the Los Angeles City Council in 1987, he had lost six of his seven political campaigns over the course of two decades.

“I don’t think I’ve lost a race,” Holden told The Times in 1987. “Maybe I wasn’t selected, but I didn’t lose the race.

Holden often enjoyed political battles at the expense of his colleagues.

“There’s nothing wrong with the competition,” he told The Times in 1987. “It’s like boxing. If you get up in that ring and you’re there yourself, you’re just going to do a shadowbox. It’s always a good thing to have a contest.

During Holden’s nearly two years of tenure on the Los Angeles City Council, he developed a reputation for sometimes difficulties as a lonely wolf. He frequently voted against the rest of the council with biased votes, and openly called his colleagues “silly”, “fake” and “lazy.”

At the time, Joan Milke Flores told The Times in 1989 that she had marked the names of all those who once opposed him in a city council vote, and approached those on his list, reminding him not to forget to vote.

“I don’t run a nursery,” Holden said. “I ask the difficult questions of bureaucrats. Hey, politics is tough business.”

When he was kicked out of the council in 2003 due to term restrictions, Times columnist Pat Morrison said LA would lose “an outrageous, showboating, 16-year franchise on Chatspa.”

But among his constituents, Holden was warmly accepted as an opponent of political establishment and an advocate for his community.

Holden represented the 10th district, primarily black, and became a spokesman for poor and middle-class people in South and Southwest Los Angeles, when neighborhoods suffered from drug and gang violence in the late 1980s. He worked to narrow down funds to increase police foot patrols to reduce crime and promote more reliable relationships between officers and residents.

He always scattered the city to roll his work into urban areas where he wrote and called letters to urban areas, including pothole fixes, tree trimming, broken street lights. He became legendary among city employees to blame them when things didn’t happen quickly enough.

“They called me Stop Sign Holden. “Because I made my district safe for pedestrians,” Holden said. “When I had to do something, I did it.”

He also wanted more parks, libraries and recreation centres in his district, and when the performing arts centre was built in the Medium City in 2003, it was named in the honor of Holden.

“Nate works harder with his members and other Los Angeles residents than please his colleagues,” then Joy Pics told The Times in 1993.

Always looking for a fight, Holden made a pass in 1989 in the mayoral seat and previously represented the 10th district as councillor, a much-likable incumbent, Tom Bradley.

Holden launched a gun buyback program of the time during the campaign, offering $300 from his campaign war chest and $300 to those abandoning their assault rifles.

Holden lost, but combined with his fierce campaign and low voter turnout, Bradley ran for his money.

“He’s a fighter,” Herb Wesson said. “If I were in the bar fight, I hope Nate Holden would be on the bar stool next to me.”

Holden’s long mission to the city council was partly cemented by the courtship of Korean-American components. Although Koreatown residents did not have a large voting block, they had fundraising power and donated a quarter of the campaign contributions they received from 1991-1994.

In return, Holden helped Korean-American business owners obtain liquor permits in Los Angeles, turning the area into one of the city’s hotspots for nightlife after businesses fled during the economic recession of the early 1990s.

“It’s Nate Holden’s legacy in Koreatown,” Charles Kim, executive director of the American Union of Korea, told The Times in 2002.

The Times investigation report revealed that many business owners who later received liquor licenses made donations to Holden’s campaign. And some saw overlap in Holden’s efforts as councillors fought so vigorously to limit liquor licenses in South Los Angeles.

Outside of politics, Holden’s tenacity was evident in other ways, such as the La Marathon, who ran at the age of 61 and 62. After the council career was over, he marched through the streets of the district, stopping all blocks and making one-arm push-ups.

“I used to run every morning in the snow in New Jersey. It was cold. I ran in front of school every morning,” Holden said. “When I came to California, I ran every morning – 5am.”

However, Holden’s long career was not without scars. In the 1990s, Holden was hit by three separate sexual harassment allegations from a former aide. The woman accused him of creating inappropriate, touching and aggressive comments and hostile work environments.

Holden fought back aggressively, winning one case in court and settling another. The third claim has been removed. However, his legal defense cost the city about $1.3 million.

He was also repeatedly fined for violating Campaign Finance Act and earning over 70 violations and a $30,000 fine. Holden admitted some of the violations, but claimed that the city’s ethics committee had put him at a higher standard than his colleagues.

Holden left the council in 2003, but was actively active in the community. At age 92, he still served on the board of directors of the South Coast Air Quality Control District, a regulator that oversees the air quality of most of Los Angeles and the Inland Empire.

Contemplating his legacy, Holden said he wanted to be remembered as a “good man.”

“I will do my best for people. Law and order. Make sure that our community is safe. I have done it all,” Holden said.

Holden is survived by his son Reginald Holden, a former Los Angeles County Sheriff’s aide, and Chris Holden, a former member of the California Council and former Pasadena mayor, as well as several grandchildren. His wife, Fannie Louise Holden, passed away in 2013 from complications from Alzheimer’s disease.

Times staff writer Clara Harter contributed to this report.

[ad_2]Source link