[ad_1]

Top Orange County prosecutors moved Tuesday to dismiss all active gang injunctions, making them the latest California jurisdiction to leave the controversial court orders of recent years.

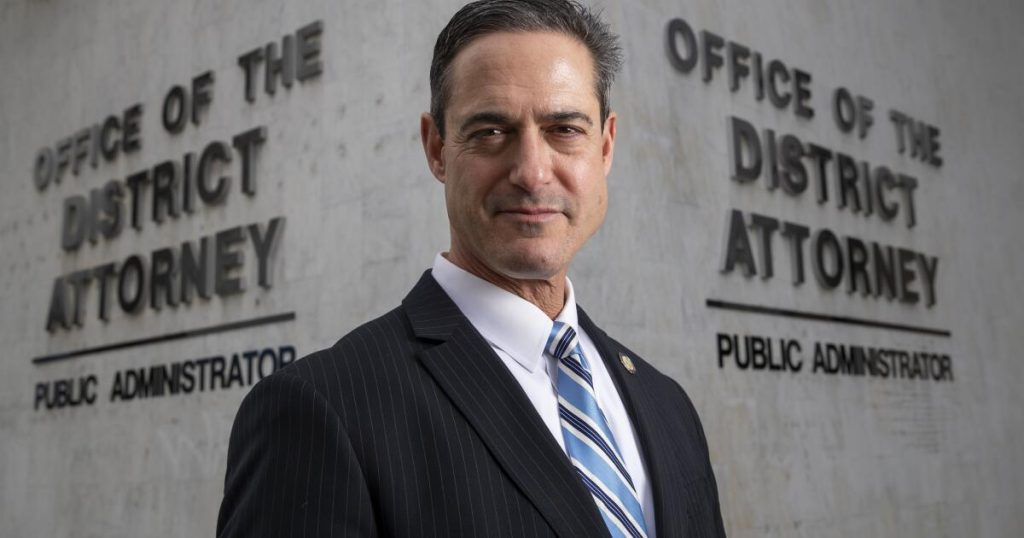

Distinguishing. Atty. Todd Spitzer said the decision came after the 2022 Congressional Bill significantly narrowed the legal definition of what constitutes gangs or gang activities in California. The injunction against the 13 gang was rejected and affected 317 people in cities such as Santa Ana, Anaheim, Fullerton, San Clemente, Garden Groves, Placentia, San Juan Capistrano and Orange. Some of the injunctions have been in effect since 2006, Spitzer said.

“We are pleased that for years of audits and years of actively removing individuals from these injunctions, these 13 gang injunctions served their intended purpose and now they are seeking dissolution,” Spitzer said in a statement. “Gangster injunctions are not intended to last for permanence. They are designed and implemented to correct criminal conduct.”

A gang injunction is a civil court order that can bar gang members suspected of working with other suspects in the same gang set in the neighborhood that are considered gang territory, from wearing certain clothing.

They were intended to suppress the ability of gangs to control their neighborhoods by marshaling in public places. A person does not need to be convicted of a crime to be subject to an injunction, but breach of the order could promote a minor emptying crime in a criminal court.

Spitzer described the move as “active,” but the district attorney’s decision came after it issued legal pressure from the Peace Justice Law Center in March. The ongoing use of the injunction argued that both California’s Racial Justice Act and the 2022 Congressional Bill Spitzer were mentioned in his news release.

Sean Garcia Reese, the center’s executive director, said the injunction was racially biased as Orange County targeted allegations of Latino crime groups despite being home to many white supremacist gangs who have never been exposed to the injunction.

“The gang injunction has turned everyday activities into generational crimes. They were built on racial profiling and intentionally used to bypass legitimate processes, and for that reason, they were abandoned in almost every county in California,” Garcia Leeds said in a statement.

“The Trump administration will use this kind of racist gang repression as a weapon to undermine legitimate processes across the country,” he said. “It’s more important than ever to ensure that all Orange County communities are treated equally under the law.”

A spokesperson for the District Attorney’s office did not immediately answer additional questions from the Times. Spitzer said his office could seek a new injunction under a revised definition of gang activity under California law if a need arises.

The relics of California’s 1990s efforts to combat a dramatic surge in gang crime have been repeatedly challenged by civil rights groups as overly widespread and Draconians, particularly as gang violence has plunged dramatically over decades.

A 2020 court settlement effectively banned Los Angeles from implementing 46 different injunctions targeting thousands of people. A few years ago, a city audit showed that more than 7,000 people were subject to the injunction.

For the past decade, officials in Long Beach, San Francisco, Oakland and San Diego have either issued reviews of the injunction program or suspended from enforcing it entirely under legal threats.

Garcia-Leys said it is nearly impossible for people to be removed from the injunction under Ex-Dist. Atty. Tony Rakkaka. However, Spitzer has enacted a review process in recent years that has led to at least 200 people being released from court orders.

Garcia Leeds said injunctions often lead to absurd restrictions. He said one of his clients was arrested by Fullerton police for stealing the trash after 10pm and violating the curfew element of one injunction.

Another was accused of violating a court order by attending family functions with his stepbrothers as both men were subject to injunctions related to the same gang and not being gathered in public.

In Los Angeles, some injunctions banned Dodgers items from wearing them at nearby Echo Park, where Dodgers Stadium is located, as baseball team jerseys were considered gangster equipment.

“I made a mistake when I grew up without a good role model in a neighborhood with a gang injunction,” Omar Montes, one of Orange County injunctions, said in a statement. “But instead of helping me, the system put me on a gang injunction.

“It was humiliating to fall into that injunction,” he said. “I felt silent and less than humans. I was regularly harassed by the police.”

[ad_2]Source link