Leaders at the University of California, the nation’s largest higher education institution receiving federal research funds, are questioning and expressing concern about the impact of the Trump administration’s suspension of research grant reviews announced this week.

The government abruptly canceled some study sessions and advisory committee meetings at the National Institutes of Health, where scientific experts gather to evaluate grant proposals before funding recommendations are finalized. NIH is the largest funder of federal research at the University of California, providing $2.6 billion in 2023-2024, representing 62% of the university’s federal awards in that year.

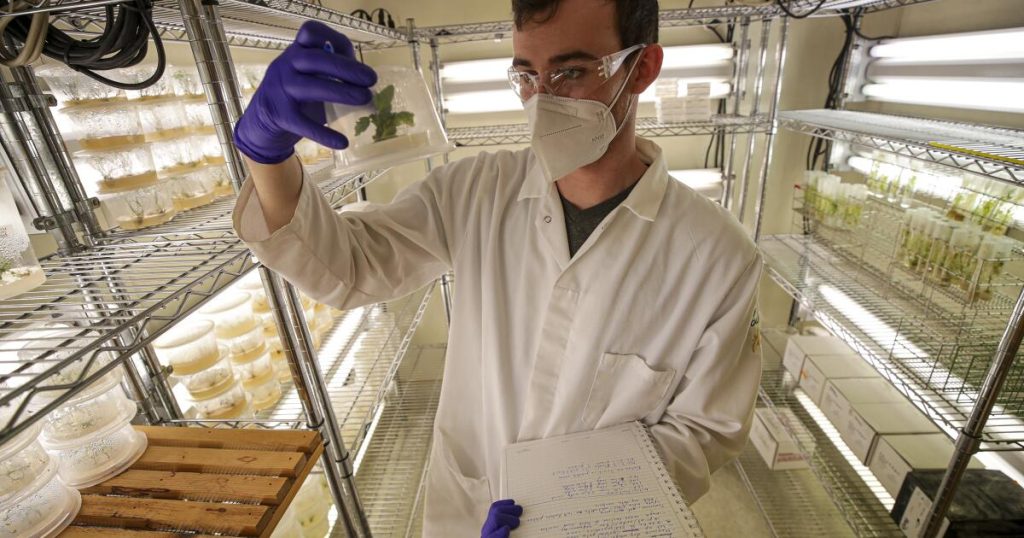

Federal funds advance UC’s vast research enterprise, including more than 10,000 grants addressing infectious diseases, brain injury, vaccination, Alzheimer’s disease, and other scientific and medical fields.

University of California leaders are trying to assess the impact of a suspension of grant reviews stemming from orders by the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Food and Drug Administration to suspend communications, travel, and public activities.

It has become standard practice for new presidential administrations to temporarily suspend operations at some government agencies while their operations are reviewed. The Department of Health and Human Services’ Jan. 21 directive said this was “consistent with precedent” and would last until Feb. 1.

Harold R. Collard, vice chancellor for research at the University of California, San Francisco, told professors that he expects to “return to normal operations soon.”

“This is not unprecedented and appears to be intended to give the new administration time to establish its leadership,” Collard wrote.

But researchers fear potentially life-changing research could come to a halt if the suspension by the world’s largest biomedical research funder continues for weeks or months beyond February 1. I am doing it.

University of California officials said Trump’s actions caused anxiety across the university system’s 10 campuses, six academic medical centers and 20 medical professional schools.

Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of California, San Diego, and the University of California, Davis, confirmed they received federal notification that their grant reviews had been suspended. One university official said he received a “cease and desist” order, leading to confusion over which parts of the research project should be canceled. Leaders of research projects are asking whether they should stop research and continue paying graduate students. Another researcher was attending an online NIH study session this week, but the meeting abruptly ended without any explanation and participants were locked out.

“There’s a lot of anxiety out there,” a University of California official told the Times. “My main message to everyone is that we have to remain calm. We are not making assumptions. We are gathering the facts.”

Christine Liu, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, said her salary is covered by the NIH, but her immediate work is not affected by the pause. But she is concerned about future research opportunities as she prepares to apply for funding.

“We all worry about our own funding and stability, which is a huge concern for long-term scientific progress,” he said. said Liu, who studies mice as part of an effort to better understand them. “Small changes in schedules can have far-reaching effects on whether a drug can be brought to market within a few years, or whether a potentially life-saving surgery or treatment in clinical trials will be available. .”

Christian Cazares, a postdoctoral fellow in cognitive science at the University of California, San Diego, who studies autism, also received funding from the NIH.

Although Cazares does not appear to have his immediate salary or research in jeopardy, he is particularly concerned about the Trump administration’s reversal of diversity, equity, and inclusion-related programs, including paid leave for federal employees in these fields. He said he was concerned about his future job because of the large amount of money he was given.

“Right now I am receiving funding. But the people who are running the program that is funding me are on paid leave. I haven’t heard it at all,” Cazares said. “I don’t know if my work will last or not.

“The NIH communications blackout feels like part of a larger transformation and attack on science, because our work, even though it is actually highly competitive and benefits society as a whole, is part of a larger transformation and attack on science. This is because there are doubts about who is being selected for the job.

A researcher at the University of California, Davis, told the Times that he was notified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that funding had been approved last week, but was informed this week that the funding was on hold.

The USDA email informed him that “the incoming administration has suspended the issuance of new subsidies.”

Other researchers said research funded by the Department of Agriculture or the National Institutes of Health has not been disrupted and they have not received any communication from the agencies indicating it might be interrupted. But two meetings with the CDC and USDA on bird flu “were canceled at the last minute,” said one researcher who was scheduled to attend.

President Trump’s directive doesn’t just affect researchers at the University of California. Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, which represents 1,600 colleges and universities, said many of his members were surprised by the sudden action. Acting Secretary of Health and Human Services Dorothy Fink announced the “immediate suspension” on Tuesday. Some researchers had already attended the conference, only to find out it had been canceled, University of California officials said.

“They’re worried about the sudden nature of the closure and frankly worried that this is a sign of things to come,” Mitchell said. “I think this campaign has generated a lot of potentially harmful rhetoric about the politicization of education and research, so we want to see whether that carries over into actual policy.”

A USC scientist in the NIH research division received word on Wednesday that an orientation meeting for new reviewers scheduled for the next day had been canceled. He said the group’s chairman had instructed them to continue working on the assumption that meetings would resume as scheduled after February 1.

With the deadline for the first funding cycle of the year approaching on Jan. 25 for several grant categories, it’s an inconvenient time to cancel meetings, but the pause in communication is manageable, Mitchell said. spoke.

But if it stretches over weeks or even months, it can pose major challenges.

Without NIH funding, “institutes will close down. University budgets are tight,” the University of Southern California scientist said. “Grants don’t just pay for experiments, they pay for training. They pay for graduate students. We’re training the next generation of scientists.”

John McMillan, vice president for research at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said that even if the moratorium were lifted on February 1, rescheduling conferences would take time and funding decisions would take at least two to three months. He said there could be a month-long delay. “Particularly for young scientists, the suspension of research and its long-term effects can be very serious.”

“Life-changing research is the driving force behind California’s innovation, and we rely heavily on federal research funding,” he said.

Some researchers worry that the Trump administration will reduce or cut funding to areas that conflict with its political ideology. The University of California’s biggest federal award last year was a $173 million grant to the University of California, San Francisco, for California’s child immunization and vaccination program, which President Trump He could become a target of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who nominated him for secretary and is anti-vaccine.

But University of California officials say the university’s research has broad bipartisan support. In fact, in 2017, President Trump’s attempt to cut NIH funding by $1.2 billion was rejected by the Republican-controlled Congress, which gave the agency a $2 billion increase.

In an email to the University of California community, Christopher Harrington, vice president for federal relations at the University of California, said: We are in close contact with 54 people, including It has been properly communicated to members of parliament and is well understood. ”

“As the University of California research leadership team, we work with both sides of the aisle, and we have really rich conversations, and our audience is nonpartisan,” said a senior UC leader.

“We value the relationships we have on both sides of the aisle because we all benefit from advancing our work.”

Source link