The one person I wanted to be with at Donald Trump’s inauguration was preparing to play cumbias when I met him outside the Pasadena Community Job Center.

Pablo Alvarado is co-executive director of the National Day Labor Organization Network, known as NDLON. The 58-year-old from El Salvador is a legend in the local immigrant rights movement, organizing a soccer league in a Los Angeles factory in the 1990s that brought together Latin American workers from different countries in nationalist confrontations. He was the one who abandoned them so they could unite under common ground. Struggling.

A former day laborer himself, he has spearheaded NDLON in nearly every fight on behalf of undocumented people in California and beyond, from sanctuary cities and state laws to the removal of immigration officials from local jails. He has helped bring it to the forefront. If anyone has advice on how to stand up to President Trump and his promise to crack down on illegal immigration, even now in the wake of the devastation of the Eaton fire, it’s Alvarado.

He and his family had to evacuate their home in Pasadena when the smoke and ash became unbearable. The next day, he organized volunteer Hornarello day laborers to clear fire debris from lawns, roads and driveways. Videos of their energetic and hilarious efforts quickly went viral, garnering international coverage and serving as a powerful antidote to President Trump’s xenophobic insults.

A promised sit-down interview was postponed multiple times until a friend said the best way to talk to Alvarado was to watch him play. So I joined him on Inauguration Day, along with workers, volunteers and others.

First, he wanted everyone to dance to NDLON’s house band, Los Hornarelos del Norte. They have been a fixture at immigrant rights rallies in Southern California for 30 years, reminding us to enjoy the good things in life and not wallow in the bad.

Wearing jeans, work boots, flannel, a black hat and a T-shirt that read “Solo el pueblo salva al pueblo” (Only the people can save the people), Alvarado played a steady bass line. The singers belted out harrowing songs about resistance and exploitation. An accordion player encouraged the crowd of about 150 people to dance, clap and chirp in approval.

“Of course he plays bass,” exclaimed Hector Flores. Flores, a member of the East Side band Las Cafe Terraces, volunteered. First, I had to help a friend bring a fancy portable toilet from Fresno.

“The base lays the foundation. It’s the anchor for everyone else to shine,” Flores explained. “That’s Pablo. Those are the people I want to be with.”

Los Hornarelos del Norte finished a short but lively set, and the bassist spoke.

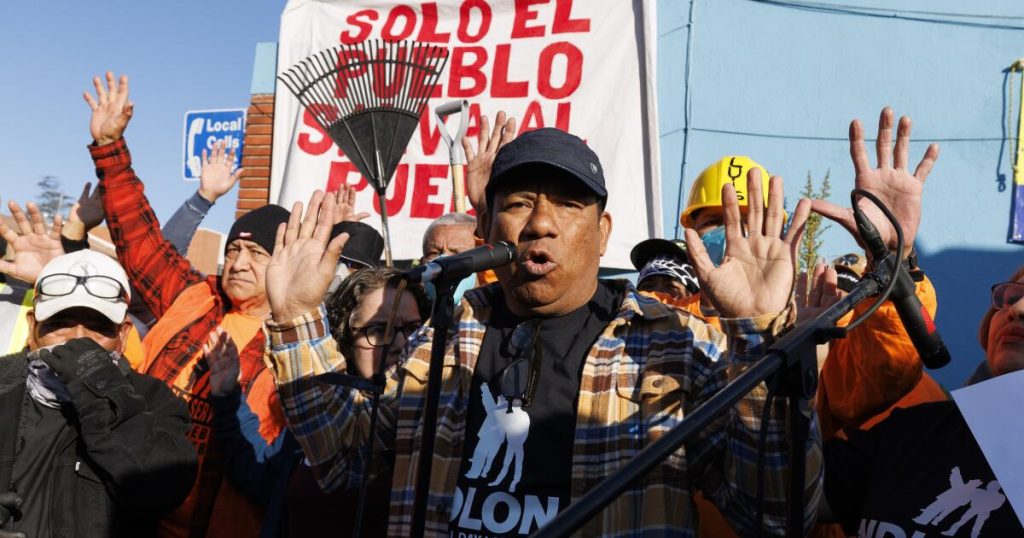

Pablo Alvarado (center), co-executive director of the National Day Labor Organization Network, bases himself before organizing a supply chain with volunteers for Eaton Fire victims at the Pasadena Community Job Center on Foundation Day. to play.

(Karlyn Steele/For the Times)

Just after 9 a.m., as President Trump took the oath of office for the second time and promised to soon send troops to the border to “repel this terrible invasion of our country,” Alvarado told the workers that Trump was literally calling the shots. asked to support. figuratively.

“Don’t be afraid, bring your tools,” he demanded in Spanish. His voice was calm and steady. About 30 people came forward. “Raise those calloused hands!”

He switched to English. “Let’s lift it up with pride, because these are the hands that will rebuild LA.”

Mr. Alvarado warned that the country would face the double whammy of a new president hostile to poor immigrants from Latin America and the unfathomable task of rebuilding from the Eaton and Palisades fires.

“Today, this is your inauguration,” Alvarado said to cheers, finally smiling. “And a day laborer is the president of this country. ‘Que Viva El Pueblo Immigrant!’

Later, people began to divide into cleaning units and organize supply chains. Crowds of people gathered to welcome Alvarado, including Pasadena resident Florence Annan.

“Pablo is like a Tasmanian devil, but he’s causing good trouble everywhere,” said Annan, a member of the Pasadena Police Oversight Commission. In 2020, NDLON marched with Annan and others to commemorate the murder of George Floyd.

“He will inspire people to join him in the journey of justice,” she added. “He’s telling them it’s long, but we need to work on it.”

Alvarado eventually broke away from the crowd and ran into the vocational center to check on NDLON’s plans for the day. Work tools, poster boards, pizza boxes, and cold coffee filled the space.

A staff member put on Ray-Ban sunglasses for Alvarado. They had hidden video cameras embedded in them. “That’s how you catch bosses who don’t pay,” Alvarado said with a big smile.

We went outside and chatted for a bit. Volunteers rushed past us with pallet jacks. The ruins were several miles up Lake Avenue, but the smell could be felt. “I lost all sense of time,” he admitted. “But what I’m going through has nothing to do with what everyone else has to deal with.”

He personally knows at least 50 families who lost their homes in the Eaton Fire, as well as others across Southern California who are now out of work because the homes they served in the Pacific Palisades, Malibu and Altadena are gone. I know hundreds of workers.

The timing, with Trump in power, could not have come at a worse time for NDLON, but Alvarado said it would still be the perfect opportunity to show opponents how to stand up to the new president. spoke.

“Whatever resistance is going to happen, it’s going to be like this,” he said, nodding at the scene before him.

Pablo Alvarado, co-executive director of the National Network of Day Labor Organizations, greets volunteer Annie Corcoran outside the Pasadena Community Job Center on Inauguration Day. The Long Beach resident is working with an Orange County-based hiking group to clean up Pasadena’s streets.

(Karlyn Steele/For the Times)

I asked what the rest of us could learn from his decades spent in the proverbial trenches.

“Don’t despair. When faced with a crisis like this or any future crisis, take it one day at a time,” he said. “How to plan in uncertain times is always very difficult. But one thing I’ve learned is that if you follow the greater good, if you follow your heart, nothing will matter. That means it won’t happen.”

I suggested that’s an easy answer, especially if President Trump wants to make life miserable for the people Alvarado has spent much of his life defending.

“What I say has never failed,” he answered calmly. “Please look around us.”

More volunteers were waiting to order. More trucks arrived with more supplies. It keeps getting better and better.

“It’s so beautiful,” Alvarado continued. “People who didn’t know each other before are now in the same position. The other day, our members worked in Central Park with five people wearing MAGA hats. [in Pasadena]. To do a job like organizing, you have to believe in people’s ability to change. People change. ”

President Trump said he plans to visit the Altadena area on Friday as well. What will he ask the new president?

“It should be a conversation, not a question,” Alvarado responded. “If he were here, he would ask me to pick up a shovel and start cleaning for the first time in my life.”

He laughed and then became serious. “I would tell him that if he wants to make this country better, he needs to not only help the humblest among us, but give them rights so that the world can It gets better.”

Annie Corcoran from Long Beach came by to say hello to Alvarado. The teacher at Saint-Jeanne de Lestonac School in Tustin had never heard of NDLON until a member of his hiking group suggested he volunteer. Corcoran was helping out that morning and hopes to hold a fundraiser at the school for the group.

“He has integrity,” she said. “That seems to be sorely lacking these days, and we’re going to need people like Pablo for months and years.”

While she and I were talking, Alvarado departed. I found him across the street in the parking lot that serves as a drive-through donation pickup site for fire survivors. A line of cars including BMWs, Nissans, shiny SUVs and beat-up sedans wound their way to the lake, even though the giveaways didn’t start for another 15 minutes.

“It looks like disorder, but there is order,” he says. “When you’re in a situation like this, people understand that.”

As we drove back to NDLON’s headquarters, Alvarado noticed a group of well-dressed men handing out business cards and flyers to survivors idling in their cars. One person was wearing a Gucci belt. Alvarado frowned for the first time all morning.

“If you’re looking for a case, that’s going to be our problem,” he told them. They denied trying to sue. He wasn’t convinced: “Now is not the time to do that. I don’t like it.”

He waved in the parking lot. “This is a great operation. This is not a business.”

One of the men asked if he was going to kick them out. Alvarado shook his head. “It’s your right to be here,” he said. “But I don’t think you should take advantage of people at a time like this. That’s up to you.”

After a few minutes, the men packed up and left.

Delma Moreno signs a mural outside the Pasadena Community Job Center after a rally for immigrant and undocumented worker rights on Inauguration Day.

(Karlyn Steele/For the Times)

Pasadena City Councilman Tyrone Hampton stopped Alvarado and hugged him. They have known each other for over 10 years. They spoke in front of a newly painted mural in Hornareros that bears the same legend as Alvarado’s T-shirt: “Solo el pueblo salva al pueblo.” Workers were signing murals as taco trucks departed to hand out free lunches.

“When I think of Pasadena helping out, I think of Pablo,” Hampton said.

While Hampton was speaking, Alvarado was already working on his next move.

Source link