[ad_1]

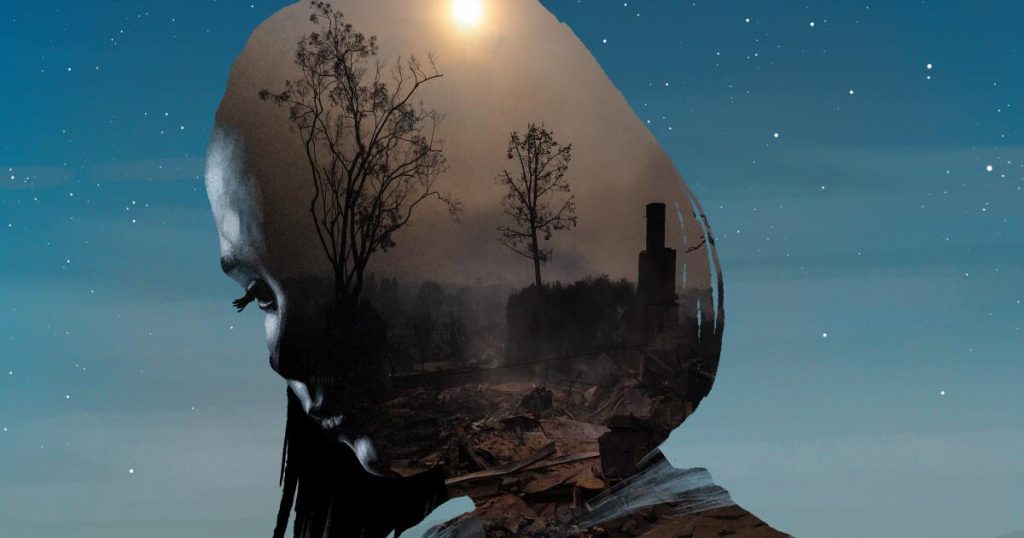

Los Angeles is a place that feels like it’s falling apart these days, both physically and mentally. For tens of thousands of people displaced, daily life is nearly impossible. Some people continue to do so with little visible change in their daily lives.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t intense inner conflicts.

How do we make sense of the fact that large parts of our cities remain untouched, while large parts of them are destroyed, destroyed, and heartbreaking?

These are confusing, paralyzing times, and above all, unfair. Smoke and ash are in the air, and so is survivor’s guilt, leaving many unsure of how to act and how to grieve.

“Everything you say feels like something you shouldn’t say,” said Shannon Hunt, 54. Her central Altadena home is still standing, but the homes nearby are not. The Aveson School of Readers, where she worked as an art teacher, has disappeared.

“Every time I cry, every time I feel like my heart is broken, I think to myself, “It’s not going to happen to me, because there are people out there who are doing much worse,” Hunt said. “That’s stupid, intellectually. I understand it’s not right, but that’s how you feel, because these people don’t have baby pictures or Christmas decorations and , because these are people I love. How can I complain?”

Experts warn that “survivor guilt” will become the new normal for many people. That’s how I felt when I was away from home for the past two weeks, when one thought struck me. “I don’t deserve this.” There were times when I tried to go to a place I frequented for solace, but to be honest, it just felt inappropriate for this moment and I left for comfort and enjoyment.

It actually shows that you are highly empathetic. Most of us don’t want to express our suffering when others are suffering more because we don’t want to make them feel bad. So whether we feel survivor’s guilt says something about us. I can tell you that we care very much about our people.

— Chris Tickner, co-owner of California Integrative Therapy in Pasadena

“That’s a huge hit,” says Mary Frances O’Connor, a grief researcher and author of “The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of Love and Loss.” “Survivor’s guilt, in many ways, is ‘I don’t deserve this.’ I don’t deserve to be saved.”

O’Connor brings up the concept of “shattered assumptions.” According to O’Connor, the term is “often used in loss and trauma research” and deals with our everyday beliefs about how life, the world, and people generally function. Masu.

“Events like loss and trauma can shatter these beliefs,” O’Connor says. “It’s not that we don’t develop entirely new ways of thinking about the world, it’s that we take time to grapple with questions like, ‘What do I deserve?'” Entire Los Angeles neighborhoods didn’t burn down; , I had to pause and consider these questions that I didn’t have to ask before. ”

admit what you’re feeling

Chris Tickner and Andrea-Marie Stark are romantic and professional partners who operate California Integrative Therapy in Pasadena. They were also residents of Altadena, and their home survived despite the destruction of everything around them, Tickner said. As therapists, they found themselves in the strange position of trying to process their own grief and survivor’s guilt while doing the same for their clients.

The first step, Tickner said, is to normalize it.

“It actually shows that you’re very empathetic,” Tickner says. “Most of us don’t want to express our suffering when others are suffering more because we don’t want to make them feel bad. It says something about us: it shows that we care about people so much that we’re willing to be stoic and not express ourselves. .”

Experts say that to begin to process survivor guilt, it helps to not only recognize one’s vulnerability but also to acknowledge and eliminate the instinct to create a hierarchy of suffering. . The first step to take is to better understand what is going on.

The LA wildfires are an incomprehensible catastrophe, and it’s natural to feel survivor’s guilt, both for those who suffered the most and for those who were relatively unscathed. At the end of the day, we all feel a sense of loss as our community and our city are forever and irrevocably changed. Nevertheless, our tendency is to keep quiet and carry on. A friend even warned me not to write this story because she thought it would be “problematic” to admit that I was struggling without being evacuated.

“The reality is that there are so many tragedies that always exist,” says Jessica Reeder, a certified marriage and family therapist at Root to Rise Therapy in Los Angeles. “I don’t think burying your head in the sand and saying, ‘Just focus on yourself’ is the right approach.”

In reality, so many tragedies always exist. I don’t think burying your head in the sand and saying “just focus on yourself” is not the right approach.

— Jessica Reeder, Certified Marriage and Family Therapist at Root to Rise Therapy in Los Angeles

One is isolation. “No matter what we’ve been through, everyone starts the session by saying, ‘I’m very lucky.’ I have no right to complain,” Reeder says. “That’s really what’s going on in my head. The collective experience of this moment, survivor’s guilt, permeates every conversation we have. It’s normal. But it’s also paralyzing. .”

turn your attention outward

Diana Winston, director of mindfulness education at the UCLA Center for Mindful Awareness Research, describes survivor’s guilt as a “collection of emotions”: “despair, hopelessness, guilt, and shame.” The longer we sit with them, the more reluctant we become to discuss them, especially about shame. Winston recommends a simple mindfulness trick called the RAIN method. The RAIN method is an acronym for “Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture.”

In a way, think of it as a beginner’s guide to meditation. “I think you can use RAIN a little bit even if you don’t have a background in mindfulness,” Winston says. “This is how I feel, and it’s okay to have these feelings. Your stomach tightens, you breathe easier, and you feel a little better. Anyone can do that with a little self-awareness.”

Take a moment and focus on the last aspect: Nurture. “Many people are feeling guilt, fear and panic. The least we can do is focus on others,” Winston says. “It helps people not lose sight of their own reactivity.”

Exercises like RAIN also help you clarify and share your emotions, which is essential. Do not bottle. The first is that it can lead us to a nihilistic place where we feel as if nothing is wrong, or it can accelerate our grief until it becomes part of our identity. Leaders say that dwelling on things can lead to a reluctance to let go and feelings of guilt for not living in the memories every day.

O’Connor says grief researchers should think about what he calls a “dual process model.”

“When we grieve, we have to deal with loss and recovery,” O’Connor says. “Recovery is about reaching out and helping your neighbors. We all need time to have a drink and cry and talk to someone who will give us a hug. The key to mental health is It’s about being able to do both, going back and forth between building and memorizing.The people who are the most adaptable are the ones who can do both.”

Take the smallest step towards comfort

It is also important to recognize what we can do at this moment.

“We have to be careful,” Tickner said. “It’s really hard to practice mindfulness right now.”

Hunt said her friends encouraged her to take time for herself. That’s not possible. “My friend said, “I have a day pass to a spa,” and maybe I can take it and relax. I said, “That’s great, but I don’t think I can do that.” “No,” he said. I would start a fuss on the table. I can’t even imagine taking a hot bath. My head is spinning. That kind of self-care just doesn’t work for me right now. ”

Restoration may mean reaching out and helping your neighbors. We all need time to have a drink and cry and talk to someone who will give us a hug.

— Mary Frances O’Connor, grief researcher and author

In such cases, says Stark of California Integrative Therapy, “simplify the conversation.” “Talk to friends, talk about how you’re feeling, write it down, make art, listen to music,” says Stark. And of course, get out and be part of the community. Volunteer work is especially comforting.

And if your friend offers help, accept it.

“We’re staying at a friend’s house right now,” Stark says. “Then the neighbors came over and said, ‘We made too much pasta.'” Want something? ‘And I started saying, ‘No, no, I can’t.’ Then I heard myself say, “I have to accept it.” It’s just pasta. ‘So I said yes and they came with a beautiful ziti and it was warm and lovely. And even though I was scared, I felt so much better.

“So please,” Stark says. “Say yes to everything people offer you.”

If you can, say yes and write, play music, or volunteer. It’s a simple tip, but Stark says it has long-term health benefits.

“Every time you do that kind of practice, you literally open up new neural patterns in your brain that expand your sense of self, your abilities, and that wonderful word we use called ‘resilience.’

[ad_2]Source link