[ad_1]

When Donald Trump signed an executive order last week to crack down on the best non-English-speaking truck drivers, there was one industry expert I had to call: my father.

Lorenzo Arerano drove a big Southern California rig for 30 years before retiring in 2019. His six-day worker kept us well and dressed us, and could afford a 3-bedroom Anaheim home with a swimming pool where he and my youngest brother still live today.

“Why does that crazy guy want to do this?” he asked me over the phone in Spanish before answering his question. “That’s why [Trump has] There was always a lack of respect for immigrants. We truckers don’t deserve this. He’s just trying to hurt people. He wants to humiliate the whole world. ”

Share

Share with intimate additional sharing options

Times columnist Gustavo Arerano talks with his father (a longtime truck driver) about an executive order by President Trump, which enforces the requirement that truck drivers be skilled in English.

Federal regulations that punish immigrant truck drivers for limited English dates dating back to the 1930s. Trump’s orders call for the enforcement of existing requirements for truck drivers to become proficient in English, and overturns a policy that inspectors should not cite or suspend Troqueros as long as they can communicate well, including interpreters or smartphone apps.

Conservatives have long linked Obama-era behavior with the rise of immigrant truckers – they now account for 18% of the occupation in a significant increase in fatal accidents over the past decade, according to census figures.

Trump’s move is the latest dog whi aimed at people who don’t like America isn’t as white as it used to be. Similarly, they follow xenophobic behaviour, such as declaring English as an official language, severely reducing birthright citizenship, and renaming the “American Gulf” in the Gulf of Mexico.

But the English-oriented push especially made me angry. If you speculate that they are the main perpetrator behind the increasing number of deadly truck crashes, the fact that they drive more miles than ever and have more trucks on the road is ignored. According to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Agency, the rate of fatal crashes is three times lower than in the late 1970s when cultural touchstones like “smokeys and bandits” burned the image of a good old white boy tracker into the American spirit.

It’s also a shame for people like my 73 year old dad.

When I was in middle school, Papi took me over the weekend and taught me the value of hard work. He woke me up at 2am so I could tie up cargo in a flatbed on a cold morning, or drag a pallet jack into the warehouse at lunchtime. I don’t remember hearing him speak anything other than the Spanish we’ve always been instructed. However, he has made it well enough that all four of his children have a college education and are working full-time.

His dream was that we both finally open our own father and son trucking company. It never happened because I was so nerd, but I was always proud of my dad’s career. He came to this country in the trunk of a fourth-grade Chevrolet and achieved his American dreams despite only picking up what I always described as a rudimentary understanding of English.

I visited my Papi the day after the phone and to see two memorabilia he can delve into from his trucking career.

Gustavo and Lorenzo Arellano talk about President Trump’s executive order cracking down on truck drivers who don’t speak the highest English.

(Albertley/Los Angeles Times)

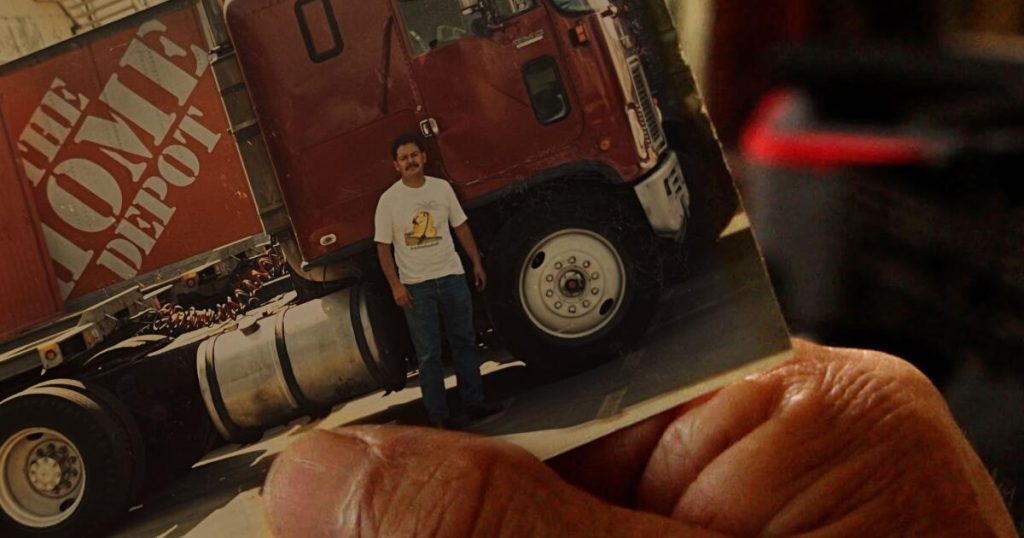

One was his bent, blurry photo of him, his first rig since the early 1990s, a faded red GMC cabover he parked behind my Tia Richa store, and he didn’t have to pay for a private lot. Papi, younger than me today, stands by Troka at Placentia Home Depot, waiting for the workers to drop it off. He doesn’t smile because the old-fashioned Mexicans don’t smile for the camera. But you can tell from his pose that he is proud of.

Other memorial papers Papi showed that it was a plaque from a trucking trade group that was in 1991. It congratulated him on “trust in your profession” and “the best thing your industry has to offer.”

“They will only give it to the drivers that were the safest,” he explained while I held it. We were sitting in his living room. There, photographs of the late mother and our children decorated the bookshelves. He broke a smile. “I got a lot of them.”

I asked him how he learned the English he knew. Papi replied that in Spanish – his first lesson was in his first job in the United States, a carpet cutting factory in Los Angeles. The owners not only taught Latino workers how to operate the machines, but also made sure that the Immigration Bureau left them alone whenever there was an attack.

Otherwise, my father would have lived in the world of my first language, the Espanyol. When he married my Mami and moved to Anaheim, she convinced him that they should take English classes at night to improve their outlook. He only stuck with it for two years “because I worked a lot.”

While he was training to become a truck driver in the mid-1980s, the instructor spoke Spanish but told everyone that he needed to understand traffic signs and learn enough English to pass the DMV test.

“And that makes sense, because this is America,” Papi told me. “But this is also Southern California. Everyone knows a little English, but a lot of people know a little Spanish too.”

I asked him how much English he used for his job.

“50%, maybe,” he replied. “Why are you going to say ‘a lot’ when that’s not true? ”

He recited the sentences in which the dispatchers and security guards kept him in English at all stops.

What are you coming for?

Which company do you work for?

Who is the broker?

What is the address?

Do you have a driver’s license?

He repeated each question – and the corresponding answers slowly took its mind, as if to remind him of a time when he was younger and happy to find his professional groove.

“They listened to me and despite me talking about Chueko y Mocho, they understood,” he said – bent and broken. Speaking this out loud, my father became characteristically self-conscious.

I asked if someone had mocked him for his English.

“No,” he said, suddenly happy. “We’re truckers, so we’re the Brotherhood.”

Papi rattled all the migrants he worked with on trucking day. Russian. Armenian. Arabs. Italian. “They didn’t know Spanish. I didn’t know their language. So we had to speak English to be friends. Everyone knew a bit.”

In fact, he recalled how immigrant truckers looked down on people who spoke perfect English.

“People who don’t speak English work hard. He doesn’t run away from work. English speakers didn’t work much because they thought knowing English made them so powerful. English speakers would say, ‘Why do I want to work late?’ And then they run to their home. ”

I asked Papi if he regrets not knowing more English.

“No. What’s going on?”

Then he took a little time. “Looking and studying is for people who like it, like you, but I am not.

He gestured around our family home. “But we had a good life. I did what I had to do.”

My dad was not the most responsible man in his personal life, but trucking grounded him. I thought that he and many other truckers sacrificed self-improvement in something like English lessons in the name of moving forward in the workplace. I remember all the inspections my dad’s rig had to go through – he never failed – and if he relies on my rearview mirror instead of my side mirror when I’m backing up, he rebels me to this day. Every time we see each other, he reminds me to check the oil and pressure on my tires.

Truck drivers are some of the most careful people you will meet. Because they know how dangerous their profession is. So for Huff’s Transport Secretary Sean P. Duffy in a press release that says his department will always put American truck drivers first – as if people like Papi don’t belong to that group – they should hate and ignorant about what trucking in this country really is about. Or what is this country really?

Dad and I were waiting for the video editor to record what he was talking about his trucking day. Finally, I dumped the idea: how about he addressing Trump on behalf of an immigrant truck driver… in English?

Wearing a fashionable black Stetson, a leather vest and his best boots, there was no way Papi could pass. He looked directly at the camera.

“Mr. Trump,” he said. “This is Lorenzo Arerano, 100% Mexican. Please respect the truck driver. We are always working hard. It doesn’t matter if they don’t speak English or not. They have to become good workers.

His heavy accents didn’t get in the way of his voice despite the president’s dislike, even more polite and even unorthodox.

“They speak a bit of English,” Papi said of his trucking aide. “Don’t need a lot of English. Listen to this conversation. Thank you Trump. Do something for us.”

I joked that this was my dad and probably didn’t speak English.

“TodoMocho. TodoChueco,” he said again.

In other words, it’s perfect.

[ad_2]Source link