[ad_1]

The immigrant attack had been going on for several days by the time Josephina and her husband spoke.

At night they could hear helicopters from a Boyle Heights house.

The couple could no longer afford to postpone the conversation – fear was increasing to the potential separation of their families. Josephina’s husband, a clothing worker, is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico.

On June 6, the couple’s 15- and 19-year-old children were texting their father in panic when US immigrants and customs enforcement officers stormed an atmospheric apparel clothing factory. He also works in a clothing factory.

Should he go to work? That’s what they had to have Tuesday night.

The couple sat in the cafeteria. Their kids were engrossed in the living room movies. Parents didn’t want their children to listen to the conversation, so they thought they were out of their ears.

They weren’t.

“Dad should just stay home,” the teen insisted.

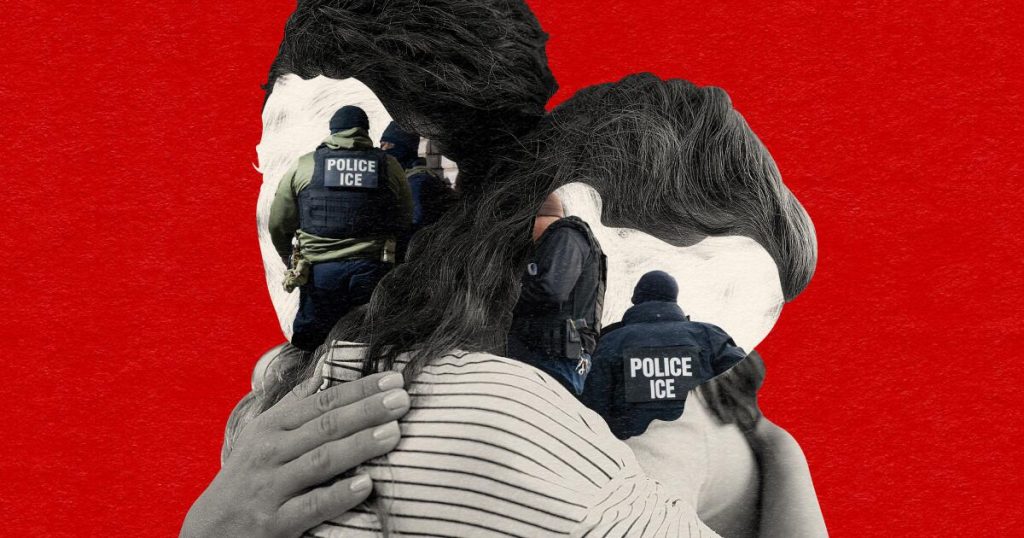

Children outside Long Beach City Hall hold a sign denounced the ice during the June 10th rally.

(Kate Sekiira/Los Angeles Times)

And that was part of a difficult conversation for the whole family. It wasn’t the way the couple wrote it, but Josephina agreed to know the kids.

“I tried my best to protect them, but they have a lot of questions,” said Josefina, who likes others in the report. “They are trying to understand what will happen after this, so what I have offered them is that this is not how things can be forever, they have the power in the community.”

Josephina’s dining room-like conversations unfold throughout the Los Angeles area. Families with undocumented members are addressing questions that have been brought to the fore by the Trump administration’s chaotic crackdown on what they call “immigration violations.”

Is mom likely to get arrested? What happens if my dad can’t go to work? These and other questions encourage excruciating and potentially life-changing, focusing on planning the possibility of family deportation.

Parents are often at odds about how much they communicate to their children, even when dealing with normal problems. But the intense anguish I felt at this moment exacerbated the dilemma.

As we dig into parenting, interim kindergarten, health, and other issues affecting children ages 5 to 5, we will be involved in journalism funded by our community.

Children’s psychologists and counselors said children should be folded for these important conversations in an age-appropriate way. In doing so, licensed clinical social worker Yessenia O. Aguirrel said it would help children to consider moments of anxiety.

“I advise people to have conversations early on,” said Aguirre, who co-develops a coloring book for parents to help them navigate the fears and anxiety associated with immigration. “Kids still have fun childhoods where they can learn about the real dangers. We don’t need to protect them from what they already hear from news, social media, and going to school.”

If there was a week when children heard about issues related to immigration, it was this past in LA.

The offensive sweep by ice has been met with intense resistance from protesters and others since June 6th. Paramount’s Home Depot was a flash point after border patrol agents began gathering there early on June 7th. This episode was one of the triggers that led the Trump administration to deploy National Guard forces to LA over Gov. Gavin Newsom’s objection.

Icefor continues to delve deep into the neighborhood, causing new rage. On Wednesday, the Times reported that a 9-year-old Torrance Elementary School student and his father had been deported to Honduras.

Protesters will meet near the Long Beach Civic Center on June 10 to seek support from families facing deportation.

(Kate Sekiira/Los Angeles Times)

The Cascade Event has created a very uncertain time for immigrant families. Psychologist Melissa Brymer said Melissa Brymer, director of UCLA-Duke National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

However, she says there are simple actions parents can take to help their children, such as organizing a comfortable family meal or other relatives check in with the youth to increase their sense of security. Even asking children if they’re sleeping soundly can spark a wider debate about how they carry them.

“Children are usually willing to talk about it from a sleep perspective,” Breimer said.

Closing the kids responsibly

Crowded around the dining room table, Josephina and her husband told the kids they would decide whether to return to work by Friday.

The kids were part of the conversation now, but that would still be an adult decision. They had to weigh the risk of workplace attacks with the likelihood of a husband’s arrest for the financial impact of losing a significant source of income. The family was trying to save money for legal defense, Josephina said, if her husband was taken into custody.

“We don’t have the money like, ‘Oh, I’m going to stop your job,'” Josephina said.

Until the teenager overhears the conversation, Josephina hopes to be enough to draw comfort from her family’s plans. She said, for example, that children know what to do with an attorney who calls if an ice officer comes to their home and their father is taken into custody.

Share with intimate additional sharing options

According to experts, it is the right instinct. Aguirre said Preteens and teenagers would “pick up our mood” and that they might understand more than their parents are aware. “They feel our insecurities, they see what we do,” she said. “They might want to see what’s underneath if we’re not talking.”

When broaching harsh topics, older children should be given “space to vent,” Aguirre said, and parents should resist the urge to tell their children not to be scared or worried right away. Instead, they can relate to it and say, “It makes sense – we are all very scary.”

Parents can also tell them they have a plan and then get clues to their children. “At that age,” Aguirre said of the teenagers, “It’s a family dynamic and it’s where they’re included.”

Some scenarios such as parental detention are bleak. But the kids have to notice them, Breimer said. “I think it’s really important to tell kids about potential separations,” she said. “The kids are worried about that, so let’s make sure we talk to them. How will the potential separation affect them?”

As for Josephina’s family, they decided that her husband, who had moved from Mexico while in elementary school about 40 years ago, would return to work. “He decided, ‘I’m still responsible and I still want to provide it,'” she said.

For her 15-year-old daughter, planning made her feel safer.

“I feel like the whole family. I’m the least afraid of what’s going on,” she said. “I think it’s because they have hope for the people in LA.”

I’m looking for normality

Anna’s son is scheduled to graduate from eighth grade on Tuesday, and amid an ongoing ice sweep, her family was struggling to see whether to attend a celebration at his Mid-Wilshire Area School.

Her husband is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. And she is the recipient of the Childhood Arrival Program Deferral Measure, a 2012 policy that provides protection from deportation to immigrants without legal status that came to the United States as a child. The program is the focus of a long legal challenge and could ultimately be deemed illegal.

Their 14-year-old son knew the interests.

“He understands what’s going on – there’s an arrest,” Anna said.

Still, the family decided to attend graduation. Still, on the morning of the event, their son wanted to revisit the decision and ask his parents if they were happy with it. He even suggested that you could watch the ceremony from your home in a live stream arranged by the school.

“I told him, ‘No, we’re going to accompany you,'” Anna said. “And we did. In the end, it was worth staying with him and praiseing him for his success.”

The experts were able to understand her decision. Maintaining a sense of normalcy can help children stay in a uniform keel if it is safe to do so. Blimers are encouraged to go to school or summer activities if possible and to participate in typical social events.

“Kids get better with routine,” she said. “They should be allowed to play and interact.”

However, Aguirre pointed out that children long for a “sense of safety and connection with their loved one” rather than wanting a “sense of normalcy.” She added: “It may not be the best time to maintain that normalcy. It puts a lot of pressure on parents.”

He said if attending public events or milestone celebrations involves a significant risk, parents may consider opting out and planning to make plans to make sure they feel their presence from afar.

“We prepare the kids in advance and say, ‘We can’t be physically there, but we’re very proud of this achievement,” Aguirre said. She said parents might say to the child, “We’re going to ask [a friend at the event] Blow this whi and know we’re there when they blow it off. ”

“If you’re in the eighth grade, you’re heartbroken that you don’t have parents there, but you can imagine that if something happens, they’ll feel a lot of guilt,” Aguirre said.

On Anna’s son’s graduation day, the school auditorium opened several hours earlier, so the family didn’t have to wait on the sidewalk. But the celebration is bittersweet, she said. The fear was evident among both students and the crowd. There were no familiar faces.

“It’s a little difficult to face sometimes,” Anna said. “But at the same time, we must be with them at these important moments in our lives.”

Give the kids an outlet

Page and her 8- and 11-year-old daughters stood in front of the Long Beach Civic Center on Tuesday evening, along with about 400 other protesters.

They chanted a slogan near the port headquarters, located among signs and swirling American and Mexican flags. “Seeking for safety is not a crime,” one indication read. “Humans are not illegal,” another said.

Families are not new to protest. Page and both daughters took him to town in 2020 after George Floyd’s murder caused rage. However, this time the issue is personal. The girl’s father is an undocumented Mexican immigrant.

“It’s a little difficult for her because it’s making a huge impact on our family right now,” Page said of the young girl. “She’s fighting for her family.”

Page is separated from the girl’s father and he lives elsewhere. It was difficult for the kids to spend the night away from him, she said. To alleviate their worries, he stayed for several nights. And attending the protests brought even more comfort as they showed that their children were part of a supportive community.

Protesters held signs outside the Long Beach Civic Center on June 10th to protest ice attacks throughout Los Angeles County a few days ago.

(Kate Sekiira/Los Angeles Times)

In times of crisis, giving children the opportunity to express themselves by participating in the moment helps them process their emotions, Breimer said.

“They love their culture, so people are protesting and they are trying to defend their rights and the rights of others,” she said.

But participating doesn’t necessarily mean protesting. Instead, children can help in other ways, such as helping deliver groceries for vulnerable neighbors.

Brymer said it’s important to acknowledge that children “really want to be agents of change.”

Sequeira reports on the Times early childhood education initiative, focusing on learning and development for California children from birth to age 5. To learn more about the initiative and its charity funders, visit latimes.com/earlyed.

[ad_2]Source link