Isn’t this just a classic Los Angeles story?

Conflicts over land — who had it, who has it now, and who will get it?

Now, it’s a battle in court over who should have the right and duty to decide the fate of hundreds of acres on the federal Department of Veterans Affairs’ West L.A. campus. For those new to this place, it’s some of the most desirable land in Westwood’s vibrant neighborhood.

By the standards of L.A. history, its story goes back a century before that, when it was first dedicated to the country’s suffering soldiers, like Queen Victoria and the first movie camera.

First, long before that, the Spanish and Mexicans wrested it from Native Americans. Then the Yankees tried and wooed the Spaniards and Mexicans to take it away. Then in 1888, the acres were set aside for disabled and destitute veterans.

The first Civil War soldier to move in was a private from New York, and he was so anxious that he couldn’t wait for the wooden barracks to be completed and pitched his tent. Some of the many fanciful gingerbread structures erected there, scandalously said to have been designed by the famous architect Stanford White, were similar to the Hotel del Coronado, which opened in the same year. .

Newsletter

Get the latest from Pat Morrison

Los Angeles is a complicated place. Fortunately, there are people who can provide background, history, and culture.

Please enter your email address

Please sign up

You may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

(Of all of these, only a small portion of the historic Wadsworth Chapel, built in 1900, is still standing. It will take millions of dollars to restore it to the condition befitting such a unique historic building.) )

These veterans were already fighting for land, fighting across Northern and Southern states, the United States against the Confederacy, and the land of the freedmen against the lands of the slaves.

At the beginning of the Civil War and about six weeks before he took his own life, Abe Lincoln created the National Housing System for Disabled American Soldiers, and this 600-acre Westwood estate eventually became the system’s westernmost outpost. It became a base.

During four years in the slaughterhouse, almost a third of the Union’s one million “boys in blue” were injured. Although not all of them were in a catastrophic situation, many were in poor physical and mental health and were unable to work or do anything. And I didn’t have a home and couldn’t find one.

And here, waiting for them was Southern California, the bright edge of the continent, the promise of care and companionship. The Yankees, wearing blue suits, were the first to appear. Hundreds of them marched from Northern California to this new billet.

Before long, we’ve come to welcome the Rough Riders and their allies, the Doughboys of World War I, the GI Joes of the “Good War,” the Korean veterans who served in conflicts rather than wars, the grunts and jarheads of Vietnam and Iraq. It became. And Afghanistan.

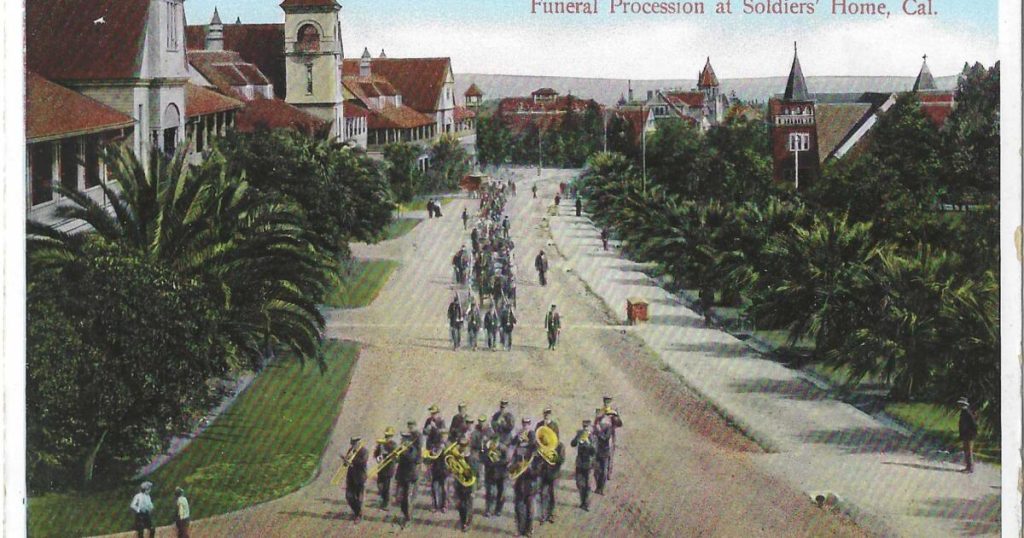

This vintage postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection depicts people lining up outside a hospital building.

What is important about the National House is that it was not only a place for charity and benevolence. To the town outside its gates, they were business. The public’s eagerness to acquire these homes was similar to today’s competition between amusement parks and giant corporations.

These ex-servicemen will need food, groceries and cigarettes in their pockets. Hundreds of things and thousands of pensions in their pockets, right? One Saturday in 1904, $80,000 arrived in the accounts of the Westwood veterans. Surely some of these will cross the gate and invade the town?

So we received a lot of offers to welcome dozens of veterans into their homes. The whole of Catalina Island was offered. The winner was a combination of carrots and sticks, with donations that were not only made out of the goodness of their hearts, but also resulted in revenue.

A terrifying trio of landowners. One of them was the philanthropist Arcadia Bandini Stearns de Baker, an heir to land by birth and marriage. her husband. and a Nevada state senator founded Santa Monica in the 1870s. In the end, their donation totaled nearly 600 acres for a site that would support veterans and help put Santa Monica and the future town of Sawtelle on the map.

The Home for Disabled Soldiers sprang up on the property, and with an abundant water supply and a $100,000 gift from a land donor, the site was transformed into a landscape of magnificent trees along artfully winding paths. It became a vast district with decoratively decorated gardens filled with lush greenery without being ostentatious. A view of vegetables and orchards.

It may have looked like paradise, but the scenery didn’t always live up to its promise. In July 1901, a doll hung near the entrance to a house with a placard on its chest reading “1/4 Master,” a quartermaster responsible for the basics of survival such as food and water. The Times dismissed it as a joke, and its owner, a Civil War veteran, dutifully reported that rumors of a grudge against Quartermaster Major J.B. Simpson were untrue. “Because of the oleomargarine shortage… [contractor’s] Wrong…there is no protest against the quartermaster. How surprised the Times must have been a month later when Mr. Simpson was suspended for what the paper had embarrassingly reported… [there is] There is no question that it reflects Major Simpson’s integrity. ”

A vintage postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection depicts the barracks of the Sawtelle Soldiers’ Home.

It had running water, a bakery, a library, and a small theater, but it was still a regular life, with a barracks system, officials, uniforms, curfews, and calls for meals and meetings.

And drinking alcohol is prohibited. As many as 3,000 men lived here at one time, and for men in various afflictions, worldly distractions beckoned: not only cigars and magazines, but also physical pleasures.

The Times cheerfully described them in March 1904:

“Yesterday, with wolf-like zeal, a horde of thugs, gamblers, prostitutes and drug dealers ambushed the gates of the Soldiers’ Home because large pensions were paid out to veterans last Saturday. Two men who came out of “gambling hell” were beaten and robbed within arm’s reach of the gate. Liquor of all ferocity and quality remained as long as money lasted, and brothels were transit stations for the town’s wild nights.

Drunk veterans can be reprimanded, fined, and even expelled from their regimental eden. A former soldier was dishonorably discharged from the Soldiers’ Home for running a gambling den just outside the gates. He was given the option of going out of business, but he chose to go out of business. He was making too much money outside the business to abandon the business.

In April 1927, during a years-long national drought known as Prohibition, the governor of this house was enforcing regulations against “drinking and other vices.” As a result, threats to “burn” began to be made. [him] “Out” wasn’t just a prank over margarine, there were nine arson attacks in a few weeks. Four years later, a federal judge thoughtfully, but perhaps unhelpfully, ruled that 28 bottles of champagne confiscated from a pharmacy not far from the soldier’s home should be donated to his former comrades.

When these soldiers died before reaching age, many were buried in the National Cemetery east of Soldier’s Home, now separated from Soldier’s Home by Highway 405. The Times often published, like a phantom roll call, the names and regiment lists of the 121st Ohio, 11th Indiana, 29th Michigan, 17th Kansas, and 10th Wisconsin.

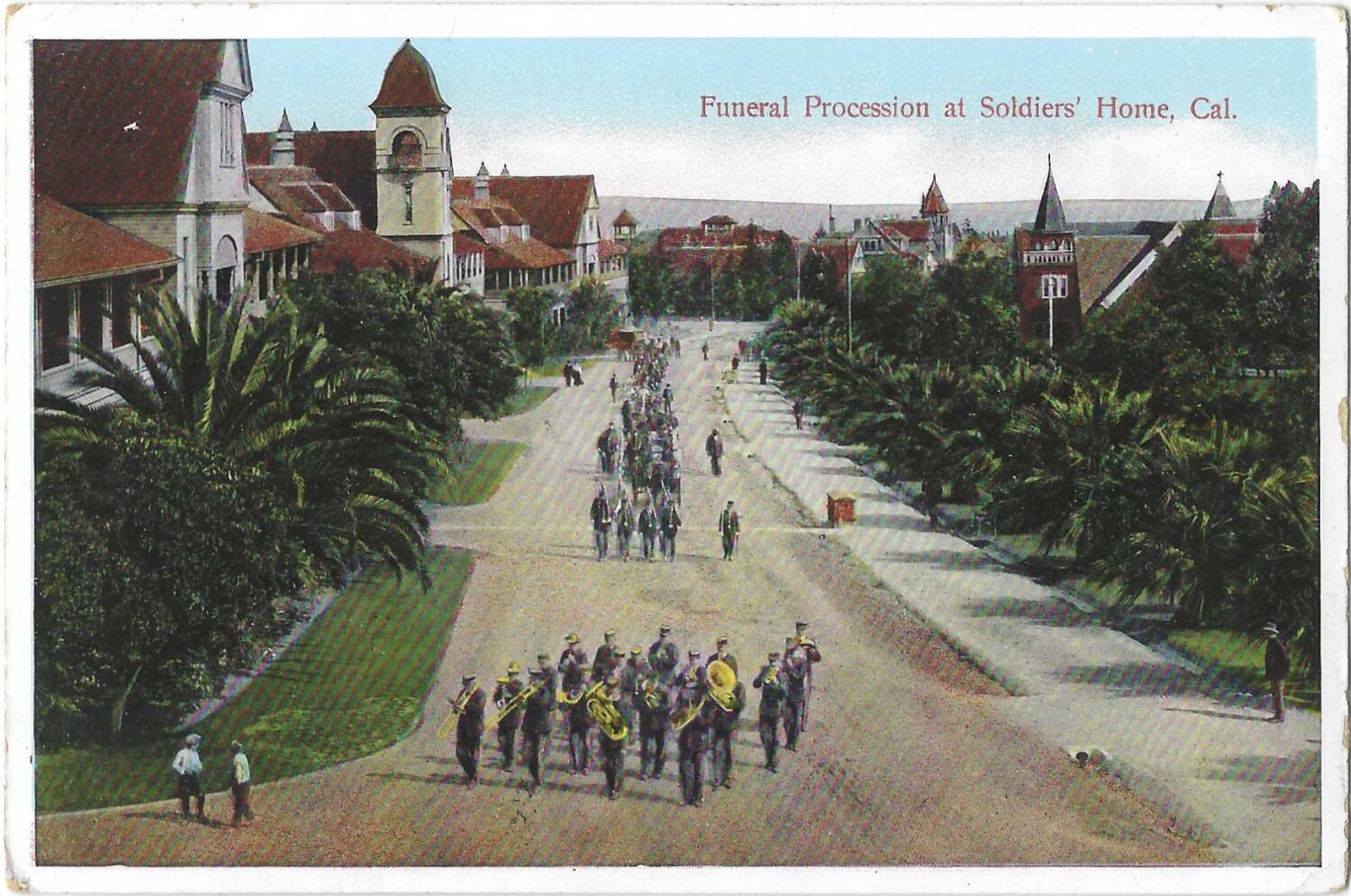

These vintage postcards from Pat Morrison’s collection depict the people and grounds of what is now known as the West LA VA campus.

But there were also enough reports of disturbing deaths by suicide and “accidents” to raise questions about what went unreported and about the depth of the iceberg’s damage, beyond Minier bullets and bayonets. .

A hundred years ago, before the exact name was found, the symptoms were unmistakable. The bloodshed and dismemberment caused by the weapons of the Civil War left these people with what we would now call PTSD, a nightmarish problem.

The close-range combat and more gruesome gun technology of the Civil War saw large numbers of soldiers cut down and “bathed survivors with the blood, brains, and body parts of their comrades,” Smithsonian magazine said in 2015. I wrote it. “Many of the soldiers were thinking about the aftermath.” He described the battle as even more terrifying, describing a landscape so strewn with bodies that they could be crossed without touching the ground. ”

In December 1902, an old soldier, said to be on the verge of death, cut his own throat on the streets of Sawtelle and died several weeks later. Around the same time, a Missouri infantryman and a local band musician, after years of sobriety, returned to his barracks and swallowed hydrochloric acid. Occasionally, veterans would wander or fall onto the streetcar tracks and either did not hear or chose not to hear the oncoming train siren.

In June 1904, a surgeon turned around after a visit to his home hospital to see a “crazy veteran” pointing a .38 gun at him. “Well, we got you,” the veteran said. He had been suffering from “imaginary complaints” ever since he was treated by a surgeon a year ago. The surgeon and two other doctors took the gun from him.

Naturally, the happy story attracted more attention. One evening in the fall of 1903, an old soldier was walking down Sawtelle Street when he heard someone say the name “Russell.”

“Which one is Russell?” he asked.

“Yes,” said one man in the crowd.

“What’s your name?”

“John.”

“Where are you from?”

“Southampton, Connecticut. Why?”

“Say the devil! Because I’m a Southampton man. Did you know Harry Russell there?”

“Yes, that’s my brother’s name!”

“Well, I’m sure it’s me!”

In the movie version, this scene would be much more risqué, but here’s the story behind it.

They were indeed brothers, John and Henry. The eldest son, John, traveled west in 1857 and ended up in Illinois, where he continued to join the Union Army and came to Sawtelle in 1900. Their second son, Henry, left home at the age of 13 with no particular place to live. He also fought in the Civil War and settled in Arizona, moving to Sawtelle in 1894. The two had not seen each other for 47 years. Like many LA stories, these two orphans made the long journey to California to find each other.

As the mechanics of war changed, so did the work at home. By the early 1960s, Wadsworth’s hospital and residence were serving more than 4,500 patients today, and the on-site neuropsychiatric hospital served an additional 2,500 patients. The 1971 Sylmar earthquake led to the decommissioning of the old hospital and the construction of new complexes on both sides of Wilshire Boulevard.

In 1930, the housing system for soldiers began to shrink. More space and care has been devoted to mental health. Treatment and research facilities began to sideline housing. Housing space was now reserved for patients, not just fallen veterans.

What a paradox! The city and federal authorities are currently working hard to find housing for the veterans. In effect, they are trying to recreate the barracks that thousands of veterans called home.

This vintage postcard from Pat Morrison’s collection is postmarked 1907 and depicts an aerial view of a soldier’s home.

Federal Judge David O. Carter, a former Vietnam Combat Marine and recipient of the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, said the Veterans Administration was tasked with the mission of the site and that it was a wealthy but illegal land grabber for the benefit of non-veterans. The court ruled that the property was rented. UCLA baseball field, private school sports facility. And he ordered the Veterans Administration to build enough housing for 2,500 people. The water must return upwards.

President McKinley visited Los Angeles and the soldiers’ homes in May 1901. Even if their faces were unfamiliar, their stories were familiar to McKinley, who had served in the Union Army.

As he concluded his address to the assembled crowd, he said something that bears repeating now that we are examining its truth. You will suffer, but you will be surrounded by all the comforts and all the blessings that a grateful nation can offer. ”

Explaining LA with Pat Morrison

Los Angeles is a complicated place. In this weekly feature, Pat Morrison explains how it works, its history and culture.

Source link